A view of University Medical Center Wednesday, Oct. 8, 2014. The Las Vegas Medical District comprises acreage around UMC and Valley Hospital and another area near Martin Luther King Boulevard and Symphony Park.

Sunday, Dec. 28, 2014 | 2 a.m.

At University Medical Center, 2014 is ending the way it started — with a new CEO.

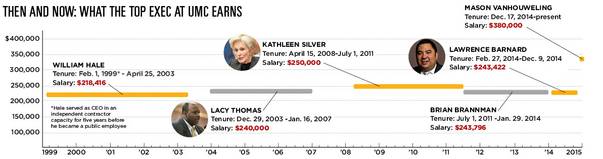

Lawrence Barnard announced this month he would leave the hospital’s top job after less than a year for an executive position with Dignity Health-St. Rose Dominican Hospitals. His predecessor, Brian Brannman, left UMC in January after two and a half years as CEO for a similar position with Dignity Health.

UMC is trying to fix the rotating door by giving a substantial raise to incoming CEO, Mason VanHouweling, whose salary was set at $380,000 when he was hired Dec. 17. That’s nearly $140,000 more than Barnard received in base pay, and VanHouweling’s three-year contract includes bonuses and incentives that could boost his annual compensation to more $500,000.

While the timing of Barnard’s departure was a surprise, it wasn’t a shock he left.

Although UMC’s CEO is one of the highest-paid public officials in Southern Nevada, the salary is a fraction of what other hospitals offer.

A recent study found the median pay for a CEO at a hospital the size of UMC is $525,000, not including bonuses and other benefits. The study found Barnard’s pay was among the bottom 10 percent of similar-sized public and private hospitals. Even with the increase, VanHouweling’s salary remains lower than 83 percent of hospital CEOs’ salaries.

Public hospitals often struggle to compete with the private sector in pay, in part because taxpayers demand that the institutions be operated at a low cost.

Factor in the added scrutiny that comes with being the head of a public institution, the political skills the job requires and the challenges of managing a cash-strapped hospital, and it’s easy to see why UMC has a hard time retaining a CEO.

“We’re in a market that places a premium on good CEOs,” said John O’Reilly, chairman of UMC’s governing board. “As evidenced by our last two CEOs that have come and gone, UMC is a popular place for other hospitals to recruit.”

The struggle to retain top talent is a problem public hospitals around the country deal with, said Dr. Bruce Siegel, president of America’s Essential Hospitals, an association for safety net hospitals.

“Often the jobs aren’t paying competitively,” Siegel said. “The salary gaps are sometimes enormous. The problem with that is not only is the pay lower, the job is harder.”

Siegel said some public hospitals decided to “bite the bullet” and increase their CEO’s pay, but that often comes with a difficult political battle. Other solutions include signing CEOs to multiyear contracts that guarantee job security or finding ways to offer bonuses for performance or longevity.

“In the long run, they’re better off with stable leadership that can run a hospital efficiency. That will save millions,” he said.

Finding extra money for UMC’s CEO is especially challenging because the hospital regularly loses money, in large part because of the uncompensated care it provides for the region’s poor and uninsured. This year, the hospital needed a $70 million subsidy from Clark County to balance its budget.

O’Reilly said the governing board is discussing ways to better compensate UMC’s chief officer, but he noted that, regardless of pay, the job remains one of the best in local health care because of the opportunity to help those who need it most.

“It is, and should be, a job that is coveted because of the fact that it has challenges true professionals look for,” he said. “You’re caring for a large population base, from those who are in our trauma unit to those who haven’t been to a hospital before.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy