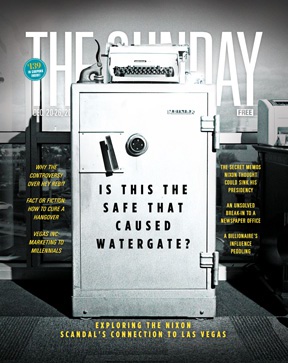

Staff file

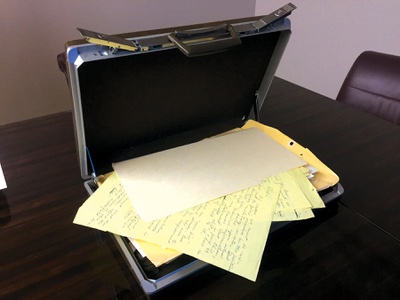

Hank Greenspun loads boxes marked “Hughes File” in his truck.

Monday, Dec. 21, 2015 | 2 a.m.

More than four decades ago, Las Vegas Sun publisher Hank Greenspun said he had information that could take down President Richard Nixon.

And in a way, he was right.

Key players

• Howard Hughes. Born the heir to a drill bit fortune, Hughes once was the wealthiest man in the world. In his early years, he ran his father’s business, Hughes Tool Company, and used it to acquire other enterprises, including a movie studio, two airlines and vast real estate holdings. Later in life, Hughes became reclusive, holing up in his bedroom, writing memos to his aides and reportedly living in filth. On Thanksgiving Day 1966, he arrived by train in Las Vegas and moved into the Desert Inn, where he stayed for four years. While in Las Vegas, Hughes never left the hotel — he never even opened the drapes in his room — but nevertheless bought the Desert Inn and five other Strip properties.

• Richard Nixon. The 37th president of the United States, Nixon resigned in 1974 after the Watergate scandal. Before Watergate, Nixon was paranoid about what might become public about his financial relationship with Howard Hughes. A loan from Hughes to Nixon’s brother, Donald, had damaged two of Nixon’s previous campaigns, and the president worried about a second sum of money, $100,000, given by Hughes to Nixon’s best friend, Bebe Rebozo.

• Hank Greenspun. Greenspun was editor and publisher of the Las Vegas Sun from when he bought the paper in 1950 until his death in 1989. Greenspun also was involved in real estate, developing Green Valley in Henderson.

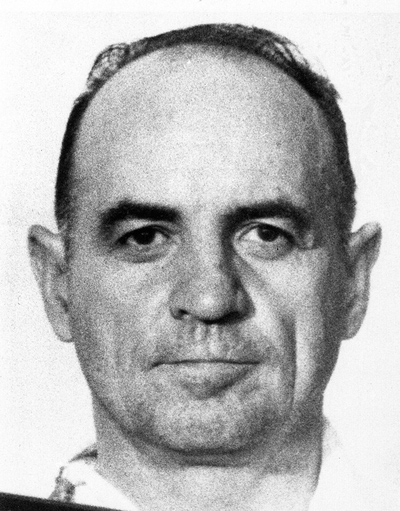

• Bob Maheu. Known as Hughes’ alter-ego, Maheu was the face of the reclusive billionaire during Hughes’ years in Las Vegas. Politicians, businesspeople and other government officials met with Maheu and considered him a direct representative of Hughes. Maheu never actually met Hughes; instead, the men communicated via written memos and talked on the telephone. Before working for Hughes, Maheu did counterintelligence work for the FBI during World War II and also for the CIA, including working on a plot to assassinate Cuban leader Fidel Castro.

Timeline of events

• Nov. 24, 1966: Thanksgiving day Howard Hughes arrives in Las Vegas on a train from Boston and moves into the ninth floor of the Desert Inn hotel.

• March 31, 1967: Hughes buys the Desert Inn for $13.3 million after refusing to leave its ninth-floor penthouse.

• Later in 1967: Hughes buys the Sands Hotel for $14.6 million, Castaways for $3.3 million and the Frontier for $23 million.

• September 1967: Hughes buys Channel 8 from Las Vegas Sun publisher Hank Greenspun.

• Dec. 27, 1968: Air West stockholders approve selling the airline to Hughes.

• 1968-1969: Hughes buys the Silver Slipper for $5.4 million and the Landmark for $17.3 million.

• April 3, 1970: Hughes acquires Air West.

• Thanksgiving, 1970: Hughes leaves Las Vegas and flies to Paradise Island in the Bahamas, where he moves into the Britannia Beach Hotel.

• December 1970: Bob Maheu is fired as head of Hughes’ Nevada operations. Maheu turns over his correspondence with Hughes to Greenspun.

• August 1972: Greenspun’s office is broken into, but the burglars are unable to open his safe, where the Hughes memos are stored.

• December 1973: Hughes is indicted by a federal grand jury in his acquisition of Air West. The indictment was later dismissed. Hughes was re-indicted again in 1974 and it was dismissed again but finally reinstated month after Hughes’ death.

• Aug. 9, 1974: President Richard Nixon resigns.

• Jan. 30, 1974: Hughes is indicted by a federal grand jury in connection with his purchase of Air West. Hughes is accused of conspiring to pressure airline directors to sell by threatening lawsuits and depressing the value of Air West’s stock.

• June 5, 1974: Personal documents from Hughes’ Romaine Street headquarters in Los Angeles are stolen. The documents later are used to write Michael Drosnin’s 1985 book, “Citizen Hughes.”

• April 5, 1976: Hughes dies on an airplane from Acapulco to Houston.

A large safe in Greenspun’s office contained a stash of memos written by reclusive billionaire Howard Hughes and his former right-hand man Bob Maheu. Nixon feared the memos might contain proof of a secret $100,000 contribution he received from Hughes. The president didn’t want the contribution becoming public because he believed that a loan his brother Donald received from Hughes had cost Nixon two elections in the past. Nixon may have used some of the funds for personal expenses.

Nixon’s fear of getting caught may have prompted some of the same people who in 1972 infamously broke into the Watergate Hotel to devise another break-in plot: one to get inside Greenspun’s safe.

They tried — or at least someone did — but the burglars failed to crack open the safe.

It was the other break-in, of course, that prompted Nixon’s resignation. But the two events were not unrelated.

Larry O’Brien, chairman of the Democratic National Committee whose Watergate headquarters was targeted in the big scandal, also had ties to Hughes. Nixon’s administration was deeply concerned about the fuzzy connection between O’Brien and Hughes, and longed to get to the bottom of it.

Also, because of a question Greenspun had asked Nixon’s press secretary months earlier, the paranoid president had reason to fear his dealings with Hughes might eventually be unveiled — and tank his presidency in the process.

At the time, no one knew for sure what the memos in Greenspun’s safe actually said, but the fear of what they might reveal proved motivating enough.

In the decades after the botched break-in, many of the memos in the safe — or at least the subjects they cover — were written about extensively. For example, the 1985 book “Citizen Hughes,” based on a cache of memos from a Hughes building in Los Angeles, references many of the memos contained in the safe. Before that, renowned newspaper columnist Jack Anderson wrote in 1974 that he had obtained a 2-inch-thick stack of copies of the memos from the safe. Some of the memos also were made public in court proceedings.

That said, any remaining mystery about the memos is about to disappear. Forty-three years after the break-ins at the Watergate and the Sun offices, Greenspun’s son Brian and Maheu’s son Peter have agreed to donate them somewhere where the public can access them.

Before they do, they are offering readers of The Sunday a glimpse inside the safe.

The memos do not appear to be what Nixon dreaded. Those reviewed by The Sunday contain no smoking gun that proves the Hughes-Nixon payoff and few mentions of Nixon at all.

What the memos do show is the extent to which Hughes sought to peddle his influence. He wanted to control politicians, to overtake rival casino owners, to put an end to atomic tests in Nevada, to own the media and more.

The memos also provide valuable insight into a man who, despite his control of a six-casino empire on the Strip, remained insulated from the general public. Hughes showed signs of mental illness, including obsessive-compulsive disorder and an extreme fear of germs. By the time he arrived in Las Vegas in 1966, he was a total recluse. Maheu never laid eyes on him.

Because Hughes was so removed from the public, his connections to the outside world were his aides, the television, newspapers — and the memos.

How Hank Greenspun got the documents

Bob Maheu gave the memos to Hank Greenspun in late 1970. The former Hughes lieutenant had been storing the documents at his house but decided he needed a creative way to get rid of them — fast.

Two related developments made Maheu feel the documents must not remain in his possession. First, Hughes skipped town around Thanksgiving, an abrupt and dramatic departure after spending four years holed up in the penthouse of the Desert Inn hotel. Then, Maheu was ousted from his post overseeing Hughes’ Nevada operations.

Maheu knew a private security firm that had been working for the remaining “Hughes people” would want access to his personal files. So he boxed a number of documents from his office at the Hughes-owned Frontier hotel and sent them to California, beyond the reach of Nevada courts.

But he wanted to keep the memos closer to home — out of his control but not destroyed.

The memos detailed many issues Maheu felt were best kept from the public eye: hints at stock manipulation in Hughes’ purchase of an airline company, Hughes’ overt racism and frank discussion of Hughes’ attempts to influence numerous politicians, to name few. Should the memos be subpoenaed, Maheu wanted to say, without perjuring himself, that he did not have them in his possession.

So Maheu and his son Peter assembled a stack of memos from Maheu’s house and stuffed them into a briefcase. Peter Maheu then hand-delivered the briefcase to Greenspun, a good family friend. Maheu watched Greenspun lock the memos inside a safe in his office. If the documents ever were subpoenaed, Greenspun could shield them from the courts by insisting they were obtained in the course of reporting.

“(He) said they’d be there safely and would remain in his possession until they were returned to us or destroyed,” Peter Maheu said. “They’ve been in there since.”

The move worked. Bob Maheu never had to turn over the memos unwillingly, and they remained secure inside Greenspun’s safe for two years.

Then, in August 1972, Greenspun’s secretary noticed something strange when she was straightening up her boss’s office. The secretary, Ruthe Deskin, saw that the window had been jimmied open and the front of Greenspun’s safe was partially torn off.

It was not a successful break-in; the intruders were unable to get inside the safe. Still, Deskin immediately called police.

Greenspun, who was wrapping up a vacation in California, had no idea who would try to crack the safe open or why. Neither did police when they came to investigate.

It remained a mystery until the following year, when a possible connection emerged to one of the biggest political scandals in U.S. history.

Congressional hearings revealed that the White House-affiliated group who broke into the Democratic National Committee offices at the Watergate was involved in other covert activities. Watergate conspirator James McCord told a Senate committee that the group also plotted to break into Greenspun’s safe.

Greenspun’s son Brian, current publisher of the Sun and The Sunday, heard the testimony.

“We’re listening to this and we’re saying, ‘Oh my God, that’s what happened in August the year before. They tried to get in,’ ” Brian Greenspun said. “All the puzzle pieces fit.”

Greenspun said he later was told by Sam Dash, chief counsel to the Senate Watergate Committee, that the Watergate scandal would not have happened were it not for the memos in the safe.

Evidence of the secret $100,000 contribution was what Nixon really feared. Hughes, via Maheu, had made the donation to Nixon’s longtime friend Bebe Rebozo. Nixon may have used at least some of the money to fix up his house in Key Biscayne, Fla.

Nixon’s administration had good reason to believe Hank Greenspun’s safe contained information about the president’s dealings with Hughes. The newspaper publisher had raised its fears earlier with one simple question.

“What happened to the $100,000 in cash that went from Howard Hughes to Bebe Rebozo?” Greenspun asked Nixon’s press secretary at an Oregon news conference in 1971, less than a year before the Watergate break-in.

Greenspun reflected on that chance encounter with Terry Lenzner, an investigative lawyer who interviewed Greenspun as part of the Watergate proceedings. Lenzner included the interview in his 2013 book, “The Investigator."

“I told Klein that the breakup of the Hughes empire in Nevada was going to sink Nixon,” Greenspun said, referring to Hughes’ abrupt departure from Las Vegas. Asked to clarify, Greenspun said he had given Klein the message that he knew about the $100,000 payment, which Greenspun characterized as a bribe.

Greenspun’s questioning brought to mind painful memories for the Hughes camp. Revelations of a previous loan from Hughes to Nixon’s brother had damaged Nixon’s 1960 presidential campaign and 1962 bid for California governor.

And if the Nixon administration had any doubts about how Greenspun knew about the Hughes cash in 1971, their questions were laid to rest the following year.

On Feb. 3, 1972, The New York Times wrote a story with the headline, “Hundreds of copies of Hughes memos are readily available in Las Vegas.” The story reported that Hughes documents had turned up in local Las Vegas publications and that Greenspun possessed the largest collection of them. The Times said Greenspun had “about 200 individual items” in his “Hughes communications collection.”

The day after the Times article was published, Attorney General John Mitchell, White House Counsel John Dean and Watergate conspirator G. Gordon Liddy discussed a possible break-in of Greenspun’s safe, according to Lenzner.

Also, Nixon spoke of the break-in with two of his aides, Bob Haldeman and John Ehrlichman, on at least one occasion, according to White House transcripts:

Ehrlichman: “McCord volunteered this Hank Greenspun thing, gratuitously apparently not …”

Nixon: “Can you tell me is that a serious thing? Did they really try to get into Hank Greenspun?”

Ehrlichman: “I guess they actually got in …”

Nixon: “What in the name of (expletive deleted) though has Hank Greenspun got with anything to do with Mitchell or anybody else?”

Ehrlichman: “Nothing. Well, now, Mitchell. Here’s — Hughes. …”

Halderman: “They busted his safe to get something out of it. Wasn’t that it? …”

Still, the identity of who tried to open Greenspun’s safe has not been proven. Brian Greenspun speculates the break-in was carried out by the Hughes organization; Peter Maheu says it seems more like the job of the Watergate burglars. No one really knows for sure.

What we do know is that the memos became intricately wrapped up in Watergate, and perhaps even caused the scandal.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy