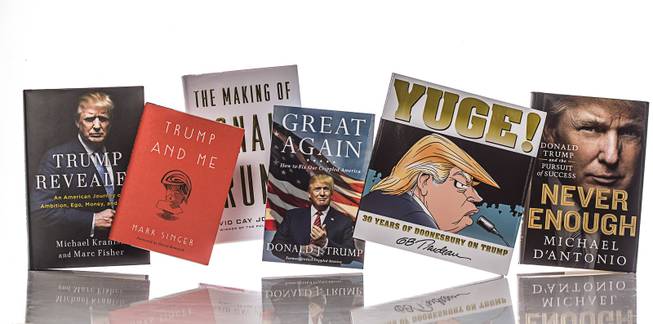

Tony Cenicola / The New York Times

Covers of books about Donald Trump in New York, Aug. 24, 2016. Accounts of Trump, among them some he wrote, describe a world where greed, arrogance and the sowing of discord are signs of leadership.

Friday, Aug. 26, 2016 | 2 a.m.

Over the past year, we’ve been plunged into the alternate reality of Trumpland, as though we were caught in the maze of his old board game, “Trump: The Game,” with no exit in sight. It’s a Darwinian, dog-eat-dog, zero-sum world where greed is good, insults are the lingua franca, and winning is everything (or, in tangled Trumpian syntax, “It’s not whether you win or lose, but whether you win!”).

To read a stack of new and reissued books about Trump, as well as a bunch of his own works, is to be plunged into a kind of Bizarro World version of Dante’s “Inferno,” where arrogance, acquisitiveness and the sowing of discord are not sins, but attributes of leadership; a place where lies, contradictions and outrageous remarks spring up in such thickets that the sort of moral exhaustion associated with bad soap operas quickly threatens to ensue.

That the subject of these books is not a fictional character but the Republican nominee for president can only remind the reader of Philip Roth’s observation, made more than 50 years ago, that American reality is so stupefying, “so weird and astonishing,” that it poses an embarrassment to the novelist’s “meager imagination.”

Books about Trump tend to fall into two categories. There are funny ones that focus on Trump the Celebrity of the 1980s and ‘90s — a cartoony avatar of greed and wretched excess and what Garry Trudeau (“Yuge! 30 Years of Doonesbury on Trump”) calls “big, honking hubris.” And there are serious biographies that try to shed light on Trump’s life and complex, highly opaque business dealings as a real estate magnate, which are vital to understanding the judgment, decision-making abilities and financial entanglements he would bring to the Oval Office.

Because of Trump’s lack of transparency surrounding his business interests (he has even declined to disclose his tax returns) and because of his loose handling of facts and love of hyperbole, serious books are obligated to spend a lot of time sifting through business and court documents. (USA Today recently reported that there are “about 3,500 legal actions involving Trump, including 1,900 where he or his companies were a plaintiff and about 1,300 in which he was the defendant.”) And they must also fact-check his assertions (PolitiFact rates 35 percent of his statements False, and 18 percent “Pants on Fire” Lies).

Perhaps because they were written rapidly as Trump’s presidential candidacy gained traction, the latest of these books rarely step back to analyze in detail the larger implications and repercussions of the Trump phenomenon. Nor do they really map the landscape in which he has risen to popularity and is himself reshaping through his carelessness with facts, polarizing remarks and disregard for political rules.

For that matter, these books shed little new light on controversial stands taken by Trump which, many legal scholars and historians note, threaten constitutional guarantees and American democratic traditions. Those include his call for “a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States” and the “extreme vetting” of immigrants; his talk of revising libel laws to make it easier to sue news organizations over critical coverage; an ethnic-tinged attack on a federal judge that raises questions about his commitment to an independent judiciary; and his incendiary use of nativist and bigoted language that is fueling racial tensions and helping to mainstream far-right views on race.

Some of these books touch fleetingly on Trump’s use of inflammatory language and emotional appeal to feelings of fear and anger, but they do not delve deeply into the consequences of his nativist rhetoric or his contempt for the rules of civil discourse. They do, however, provide some sense of history, reminding us that while Trump’s craving for attention and use of controversy as an instrument of publicity have remained the same over the years, the surreal switch of venues — from the New York tabloid universe and the world of reality TV to the real-life arena of national and global politics — has turned formerly “small-potatoes stakes,” as one writer put it, into something profoundly more troubling. From WrestleMania-like insults aimed at fellow celebrities, Trump now denigrates whole racial and religious groups and questions the legitimacy of the electoral system.

A “semi-harmless buffoon” in Manhattan in the waning decades of the 20th century — as the editor of The New Yorker, David Remnick, terms the businessman in a foreword to Mark Singer’s book “Trump and Me” — has metamorphosed into a political candidate whom 50 senior Republican national security officials recently said “would be the most reckless president in American history,” putting “at risk our country’s national security and well being.”

Two new books provide useful, vigorously reported overviews of Trump’s life and career. “Trump Revealed,” by Michael Kranish and Marc Fisher of The Washington Post, draws heavily on work by reporters of The Post and more than 20 hours of interviews with the candidate. Much of its material will be familiar to readers — thanks to newspaper articles and Michael D’Antonio’s 2015 biography (“Never Enough: Donald Trump and the Pursuit of Success”) — but “Trump Revealed” deftly charts his single-minded building of his gaudy brand and his often masterful manipulation of the media.

It provides a succinct account of Trump’s childhood, when he says he punched a teacher, giving him a black eye. It also recounts his apprenticeship to a demanding father, who told him he needed to become a “killer” in anything he did, and how he learned the art of the counterattack from Roy Cohn, Joseph McCarthy’s former right-hand man, whom Trump hired to countersue the federal government after the Justice Department brought a case against the Trump family firm in 1973 for violating the Fair Housing Act.

“The Making of Donald Trump” by David Cay Johnston — a former reporter for The New York Times who has written extensively about Trump — zeros in on Trump’s business practices, arguing that while he presents himself as “a modern Midas,” much “of what he touches” has often turned “to dross.” Johnston, who has followed the real estate impresario for nearly three decades, offers a searing indictment of his business practices and creative accounting. He examines Trump’s taste for debt, what associates have described as his startling capacity for recklessness, multiple corporate bankruptcies, dealings with reputed mobsters and accusations of fraud.

The portrait of Trump that emerges from these books, old or new, serious or satirical, is remarkably consistent: a high-decibel narcissist, almost comically self-obsessed; a “hyperbole addict who prevaricates for fun and profit,” as Singer wrote in The New Yorker in 1997.

Singer also describes Trump as an “insatiable publicity hound who courts the press on a daily basis and, when he doesn’t like what he reads, attacks the messengers as ‘human garbage,'” “a fellow both slippery and naive, artfully calculating and recklessly heedless of consequences.”

At the same time, Singer and other writers discern an emptiness underneath the gold-plated armor. In “Trump and Me,” Singer describes his subject as a man “who had aspired to and achieved the ultimate luxury, an existence unmolested by the rumbling of a soul.” Kranish and Fisher likewise suggest that Trump “had walled off” any pain he experienced growing up and “hid it behind a never-ending show about himself.” When they ask him about friends, they write, he gives them — off the record — the names of three men “he had had business dealings with two or more decades before, men he had only rarely seen in recent years.”

In his books, Trump likes to boast about going it alone — an impulse that helps explain the rapid turnover among advisers in his campaign, and that has raised serious concerns among national security experts and foreign policy observers, who note that his extreme self-reliance and certainty (“I’m speaking with myself, number one, because I have a very good brain”) come coupled with a startling ignorance about global affairs and an impatience with policy and details.

Passages in his books help illuminate Trump’s admiration for the strongman style of autocratic leaders like Russia’s Vladimir Putin, and his own astonishing “I alone can fix it” moment during his Republican convention speech. In his 2004 book, “Think Like a Billionaire,” Trump wrote: “You must plan and execute your plan alone.”

He also advised: “Have a short attention span,” adding “quite often, I’ll be talking to someone and I’ll know what they’re going to say before they say it. After the first three words are out of their mouth, I can tell what the next 40 are going to be, so I try to pick up the pace and move it along. You can get more done faster that way.”

In many respects, Trump’s own quotes and writings provide the most vivid and alarming picture of his values, modus operandi and relentlessly dark outlook focused on revenge. “Be paranoid,” he advises in one book. And in another: “When somebody screws you, screw them back in spades.”

The grim, dystopian view of America, articulated in Trump’s Republican convention speech, is previewed in his 2015 book, “Crippled America” (republished with the cheerier title of “Great Again: How to Fix Our Crippled America”), in which he contends that “everyone is eating” America’s lunch. And a similarly nihilistic vision surfaces in other remarks he’s made over the years: “I always get even”; “For the most part, you can’t respect people because most people aren’t worthy of respect”; and: “The world is a horrible place. Lions kill for food, but people kill for sport.”

Once upon a time, such remarks made Trump perfect fodder for comedians. Though some writers noted that he was already a caricature of a caricature — difficult to parody or satirize — Trudeau recalled that he provided cartoonists with “an embarrassment of follies.” And the businessman, who seems to live by the conviction that any publicity is good publicity, apparently embraced this celebrity, writing: “My cartoon is real. I am the creator of my own comic book.”

In a 1990 cartoon, Doonesbury characters argued over what they disliked more about Trump: “the boasting, the piggish consumption” or “the hideous décor of his casinos.” Sadly, the stakes today are infinitely so much huger.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy