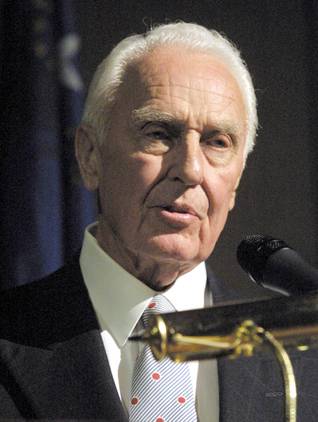

Financier Parry Thomas speaks during his induction into the Nevada Business Hall of Fame, presented by the UNLV College of Business, Thursday, February 21, 2002 at the MGM Grand Conference Center.

Friday, Aug. 26, 2016 | 5:31 p.m.

If not for visionary banker E. Parry Thomas, Las Vegas would have been a much less successful place than the thriving, sprawling, glittering desert oasis it is today.

Iconic resorts like the Sahara and Dunes likely would have had no one to finance them at the time they were built or enlarged. Thomas financed such gaming visionaries as Steve Wynn, launching him on a gaming career that included construction of the Mirage, Treasure Island, Bellagio and Wynn Las Vegas.

Thomas, a passionate supporter of UNLV whose name graces the Thomas & Mack Center, bought hotels and other property on behalf of reclusive billionaire Howard Hughes and started a foundation that fueled significant expansion of UNLV. Thomas also funded construction of Sunrise Hospital and Medical Center, which has treated millions of patients, and the expansive Boulevard mall that provided Las Vegans with one of their first centralized mega-retail facilities.

Thomas, longtime chairman of Valley Bank — now Bank of America — and the first banker to make loans to bolster Las Vegas’ gaming industry, died Friday, Aug. 26, 2016, surrounded by his wife and children at his horse ranch in Hailey, Idaho. Thomas, who was 95, also was a resident of Las Vegas at the time of his death.

Services are pending.

“I think I can trace every one of the wonderful opportunities (I) had to the advice of this man," said Wynn, referring to Thomas during a 2002 interview preceding both men’s enshrinement in the Nevada Business Hall of Fame. At the event, Thomas called Wynn “my fifth son.”

Thomas’ oldest son, Peter M. Thomas, now co-managing partner (with brother Thomas) of Thomas & Mack Co., a major real estate development firm, said his father's legacy included his family, his four-decade business partnership with Jerry Mack, his acquiring land that quadrupled the size of UNLV and his initiative to finance casino projects that forever changed Las Vegas’ skyline.

“What my father started with Jerry Mack has developed into a business that thrives and is run by not only my father’s children, but Jerry’s (and his widow Joyce’s) children,” Peter Thomas said. “We are one family, and it all resulted from Jerry and Dad being a great team — Jerry handling the real estate end and my father doing the banking.”

In the 1950s, when Thomas was a 33-year-old executive working for the Continental Bank & Trust Co. of Salt Lake City under banking legend Walter Cosgriff, he was sent to the then tiny, dusty and mostly underdeveloped town of Las Vegas to check it out for investment potential.

In those days, bankers were unwilling to invest in Las Vegas casino development because of the obvious risk involved with sinking money into gambling houses and because of the seedy mobsters who were running the casinos at the time.

But Thomas saw the casino operators as a new breed of aggressive businessmen who, despite their criminal pasts, were trustworthy.

In a 2002 interview with the Sun, Thomas said the operators of that era had an “insatiable appetite for loans.” He called them former illegal gamblers who came to Las Vegas to become legitimate. And to a banker looking to get his loans repaid, Thomas said these “characters” were about as good as borrowers would get.

“They were probably the most honorable people I ever met,” Thomas said. “Their word was their bond.”

As a result, Thomas saw practically unlimited potential in financing what would become Nevada’s chief industry. Along with his banking business partner of 43 years, the late Jerry Mack, Thomas spearheaded Valley Bank’s efforts to fuel the early expansion of the Strip.

Thomas and the Bank of Las Vegas, a forerunner of Valley Bank, made the institution's first gaming loan in 1955 — $750,000 to Milton Prell so he could finish turning his old Club Bingo into the Sahara Hotel and Casino (now SLS Las Vegas).

Prell used Thomas’ money to build what would become the famed Congo Room and add 120 rooms to the small resort, which Prell had begun transforming into the Sahara in 1952 with his own money after other bankers refused to loan him the funds.

Thomas continued investing in resorts, including the Stardust, Sands, Riviera, MGM and New York-New York in the decades that followed.

In addition to getting his own bank to invest in Las Vegas resorts throughout the last half of the 20th century, Thomas persuaded insurance companies and controllers of the Teamsters Central States Pension Fund to invest millions of dollars into Las Vegas in the 1960s and ‘70s.

Although it was later learned that Teamster pension funds were influenced by the mob, many of the resorts that were erected in Las Vegas most likely never would have gotten off the drawing board had that money not been made available to them — and repaid at a higher interest rate than what was required of loans made to nongaming companies back then.

By the mid-1970s, other banks took Thomas’ lead and began investing in Las Vegas hotel-casinos. For the most part, those institutions have enjoyed excellent returns on their investments ever since.

In 1965, Thomas became the chief proponent in changing an antiquated state law that had virtually prevented publicly held companies from acquiring casinos because every stockholder then was required to obtain a gaming license.

Despite some opposition from Northern Nevada casino owners, including the powerful William F. Harrah of Harrah’s Casino, Thomas forged ahead. Thomas eventually convinced Harrah that it was in his company’s best interest to support Thomas. The law passed in 1967, requiring only those investors with 10 percent interest or more to be licensed.

Amended in 1969, the law opened the floodgates of change and ushered in the corporate age in Las Vegas at a time when the last of the mob bosses who had run the town were being arrested and convicted or otherwise chased out of Nevada’s gaming industry.

When Howard Hughes came to Las Vegas in November 1967, he sought out Thomas to serve as his consultant on his mass purchases of Southern Nevada real estate, including six hotel-casinos and thousands of acres of undeveloped land.

At the time, Hughes was residing in a floor of suites at the Desert Inn. Thomas also moved into that Strip resort for a time so he could conduct business for Hughes, which included buying land from sellers who were unaware that he was making the purchases for the then-world’s richest man so he could keep the sale prices fair and reasonable.

The late Robert Maheu, a former U.S. spy, ex-FBI agent and Hughes’ alter-ego who also was directly involved in all of Hughes’ casino and other real estate, once said that he could not remember any major Southern Nevada acquisition that Hughes approved without first consulting with Thomas.

In 1968, Bank of Las Vegas merged with Valley Bank of Reno and became known simply as Valley Bank. In 1992, Valley Bank was bought by BankAmerica Corp.

At the time of that purchase, Valley Bank had $630 million in outstanding loans to gaming companies and its stockholders had a whopping $400 million in equity thanks largely in part to Thomas’ diligent work and foresight.

Nowhere was that more evident than in the early 1970s, when Thomas loaned Wynn $1.2 million so that Wynn could buy a narrow strip of land on Flamingo Road near Caesars Palace.

When Wynn, who at the time was virtually unknown, announced shortly after the purchase that he was going to build the world’s narrowest casino resort on the site, Caesars officials bought him out for $2.25 million. Wynn repaid Thomas’ loan and used the profits to buy a large interest in the downtown Golden Nugget, eventually taking total control of that property.

Thomas’ decision to invest in the young entrepreneur eventually launched a gaming dynasty — Mirage Resorts Inc. — that was bought out by MGM Grand Inc. for $4.4 billion in 2000. A short time later, Wynn used those profits to buy the Desert Inn property, implode the pioneering resort and build the posh Wynn Las Vegas on the site.

By 1975, Thomas was overlooking the vast business empire he had helped create from his office on the 17th floor of the $15 million Valley Bank Plaza in downtown Las Vegas.

"When it came to deciding whether to give someone a bank loan, Dad judged the applicant more on his character and less on his finances," Peter Thomas said. "Bankers can't do that nowadays."

Born June 29, 1921, in Ogden, Utah, Thomas was the son of a successful plumbing contractor. Thomas' first job was as a bank loan collector, and he served as a U.S. intelligence agent in Europe during World War II.

After the war, Thomas returned to banking and in the early 1950s went to work for Cosgriff’s Continental Bank & Trust Co., which owned interest in the Bank of Las Vegas An admitted risk-taker who soon proved he could readily identify a golden opportunity, Thomas relished the chance to work in Las Vegas full-time with Jerry Mack.

The two had been introduced to each other by Jerry’s father, Nate Mack, then chairman of the Bank of Las Vegas, who suggested that Jerry and Parry become business partners. After Cosgriff died in 1961, Thomas was promoted to president of the Bank of Las Vegas.

Thomas and Mack long had an interest in developing UNLV into a major U.S. educational institution. In the 1950s, Mack worked with Maude Frazier and Archie Grant to establish Nevada Southern College, which became UNLV.

Years later, when Thomas and Mack were looking to buy real estate near UNLV for a computer complex, they found that UNLV had just 55 acres available on campus. The duo knew that by the time the university was ready to expand, the price of land around the college would be too expensive for school officials to afford.

As a result, the two bankers formed the Nevada Southern University Land Foundation, then funded it with loans to acquire 300 acres around the Maryland Parkway institution. The land was then sold in the coming years to the university at Thomas’ original cost after state officials identified funds for expansion.

The school thanked the pair by naming the huge campus basketball arena — the Thomas & Mack Center — in their honor.

When Jerry Mack died in 1998, Thomas told the Sun in a phone interview from Idaho, “Jerry was truly grounded as a citizen of Las Vegas and wanted to do all he could for the good of the community.

“We had a fantastic partnership of 43 years. I can't recall a cross word between us. … He was a man of total integrity and an intense family man.”

A philanthropist and community civic leader, Thomas helped establish the United Way of Southern Nevada to serve as an overseer of the distribution of funds to local charities.

Thomas told much of his life story in the 2009 book "Quiet Kingmaker of Las Vegas: E. Parry Thomas" by Jack Sheehan.

Thomas is survived by his wife, Peggy C. Thomas, of Las Vegas and Hailey; four sons, Peter M. Thomas, Roger P. Thomas, Dr. Steven C. Thomas and Thomas A. Thomas, all of Las Vegas; a sister, Jane Sturdivant, of Hailey; 13 grandchildren; and 9 great-grandchildren.

Ed Koch is a former longtime Sun reporter.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy