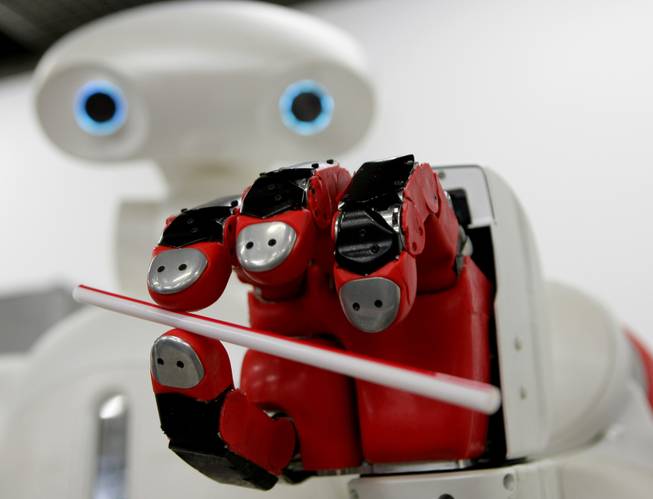

AP Photo/Shizuo Kambayashi

Twendy-One demonstrates its ability to hold delicate objects with a drinking straw. Since its 2009 debut in Japan, much more sophisticated humanoid robots have been displayed at the annual CES in Las Vegas, prompting questions about potential use in the hospitality industry.

Monday, July 11, 2016 | 2 a.m.

Every January, the modern-day Masters of the Universe flock to the Strip. From Wall Street and Silicon Valley they come for CES, where the Fetty Waps of the world play Google after-parties, and heavyweights from Intel to IBM showcase the future’s infrastructure. It’s the biggest trade show in a city of trade shows.

But are the technological leaps on display a threat to the foundations of the Las Vegas economy?

Through a particular lens, the answer is yes. With power concentrated in entrenched industries, and the deal-makers ruling from the top on down, disruption can be especially thorny. Take the taxi establishment’s strong attempt to block the infiltration of Uber and Lyft.

Intensifying the challenge for new tech is the fact that Las Vegas is defined by brick-and-mortar businesses. The machine runs on tourism standard-bearers: resorts in the center of the action, not Airbnbs on the suburban periphery; and tossing cards on the felt of a casino table, not an iPhone screen. Even if a spark starts on a dating app, the goal is to meet on a club’s dance floor.

Tourists come for the here and now of the Las Vegas experience. When locals hit the Strip, many are after that classic sense of place.

Yet the city has something fundamental in common with bullish tech upstarts. It was built on being disruptive — on the stylish glorification of gambling when it was illegal elsewhere. The brick-and-mortar soul of that might be Las Vegas’ greatest asset, but the same thing makes it vulnerable to automation, virtual platforms like online betting or immersive video games that have little in common with the slot machines lining casino floors.

“The slot floors that you see today are not going to be in existence 10 years from now,” Jim Murren, CEO of MGM Resorts International, told the Baltimore Sun last year. He was nodding to the fact that over the next decade, millennials will emerge as one of the largest generational groups visiting Las Vegas. It’s not that they don’t like to gamble; they’re just after experiences that defy the norm.

As technology’s impacts deepen, some industries will face cataclysmic upheaval while others adapt to a new normal. Las Vegas has proven adept at adapting in the past, and faced with the integration of robot workers or e-sports, no doubt it will adapt again. But with all changes, there are growing pains.

Uber and Lyft smash through a brick wall

On May 29, 2015, dozens of union taxis went idle. Drivers instead gathered on the Strip to protest Uber, which was seeking legislative approval to re-enter Nevada. It marked the start of a contentious summer in a high-profile battle with an outside tech firm.

The State of Uber and Lyft

The companies are in litigation, contesting the Las Vegas City Council’s annual $100 licensing fee for their drivers.

It’s possible that taxi companies will push for more regulatory measures, such as FBI background checks for Uber and Lyft drivers. Were they to succeed, it could drive the companies out of Nevada. Uber recently left Austin, Texas, when the city imposed a similar regulation.

Seeing a threat to its revenue stream (and possibly its survival), the taxi industry expressed concerns to the Legislature and Clark County officials about how ride-hailing outfits would be legalized and regulated here. What was at stake was its near-monopoly on transportation for hire in Las Vegas, from the Strip to McCarran International Airport.

The taxi industry had long been a power player in the state. It became regulated in the ’60s after violence broke out between drivers from different companies, but the regulation left leading companies plenty of room to protect their business. The cab companies had also developed relationships with local and state political figures, doling out regular campaign contributions. All was going well, until Uber crashed the party.

“You are doing things that are upending old, pretty entrenched mechanisms that have detailed regulatory schemes,” said a ride-hailing lobbyist whose company did not authorize him to speak on the record. “It’s hard.”

The outsiders had no inflated expectations. With the “storied history” of its incumbent industries, Las Vegas would be tough to crack. “We were aware we were coming into a market where those industries had been operating for a long time,” said Uber spokeswoman Taylor Patterson.

What About Airbnb?

Airbnb is technically illegal in unincorporated parts of Clark County, though commissioners have flirted with the idea of legalizing it, despite concerns about short-term rentals turning into “party houses.” The city of Las Vegas does allow short-term rentals but requires homeowners to obtain a $500 annual permit. Still, there has been no formal crackdown on violators. And if the app-based service poses a threat to resorts and hotels in Las Vegas, those businesses haven’t pushed back much. Airbnb lists more than 300 rentals in the Las Vegas area.

In addition to flexing their political muscle through strategic donations and lobbying, taxi companies made a show of arguing that because of different licensing requirements, Uber and Lyft drivers could be threats to public safety. This stance initially resonated with some regulators and politicians, as Uber had launched in late 2014 without licensing and was forced to leave after a judge granted a state-sponsored injunction. The focus then turned to furious lobbying. Proposals were floated to force Uber to require FBI background checks (a nonstarter that has prompted the company to leave other cities), but it was scrapped in the final regulation. After a regulatory back-and-forth in Clark County, Uber and Lyft were back on the road by September.

The app-based services were destined to win because of one simple fact: They’re popular, and that’s a compelling argument in a town that relies on being a globally popular destination. Consumers wanted — and lobbied for — Uber and Lyft, regardless of the existential risk to the taxi business woven into the fabric of the Strip. Where once there was only a cab queue, now there were zones for the ride-hail giants. And big players in the entertainment space have joined them in promotional partnerships, whether it’s Lyft and concert promoter AEG Live or Uber and Electric Daisy Carnival operator Insomniac Events.

Combined, the services now boast more drivers than the taxi collective in Clark County. But the challenge posed by their digital platforms only touched an ancillary segment of the Las Vegas economy. Transportation supports the primary drivers: gaming and hospitality. So what happens when technology impacts that powerful core?

Hospitality, minus the humanity

“Would you play cards with that creepy robot?” That’s the headline Bloomberg slapped on a December story about Paradise Entertainment, the Hong Kong company behind a prototype of a humanoid dealer named “Min.”

Segway has a robot butler. Hilton is testing a concierge powered by artificial intelligence. And a California business is developing an R2-D2-like bellhop that delivers to hotel rooms.

These technologies wow at CES, but spark questions as to what extent the Strip might adopt them. Several regional casino operators already have embraced automation in basic services. This year, Caesars Entertainment installed self check-in kiosks, and Aria unveiled in-room tablets that can be used to order food or close the curtains with a touch. They’re marketable ways to boost efficiency and cut costs, but these conveniences come with some fear of job losses tied to the vision of robots swarming the hospitality workforce.

“That’s the question everyone asks,” said Robert Rippee, director of the Hospitality Lab at UNLV’s International Gaming Institute. For now, he believes replacing human workers with robots would be cost-prohibitive. “From an economic perspective,” he said, “it doesn’t make a lot of sense.”

Rippee notes that most robots are not humanoids, and that the first iteration in the hotel space will be far duller than one might expect, with robots performing service-based functions such as translation or delivery. While flashier technology exists, Rippee said it’s in its infancy. “In many cases, it will be (about) making humans more effective,” he said, “allowing them to focus on ... what guests really like, which is interaction.”

Paul Oh, a UNLV professor of mechanical engineering who has studied robotics for 20 years and worked with industry leaders including Boeing and the Office of Naval Research, said organizations would be drawn to robots that improved service.

“I imagine maintaining and/or elevating customer experiences is always on the forefront,” Oh wrote in an email. “As such, robots (that) can add value to these experiences, while reducing costs, will be in demand.”

Oh pointed to robotic-arm bartending systems and humanoid concierges on cruise ships and in some hotels.

Even if robots don’t replace human workers outright in the short term, it is possible they could affect jobs on the margins. Three new automated bartenders mixing drinks could mean one fewer bartending job in a casino, a fact not lost on the state’s chief economic development officer.

Human Workers vs. Robot Workers

As the American economy shifts to integrate more technology, some researchers have made predictions about the cost-value of adding robots to reduce human labor. It depends largely on the industry.

Take manufacturing, for instance, where robots have been replacing human labor for some time. Research from the Boston Consulting Group last year suggested that globally, the average manufacturing firm would likely pay about 16 percent less on labor in 2025 by moving to robots.

That industry differs greatly from hospitality, which relies on direct communication and interaction with customers, requiring critical thinking and emoting that are difficult (if not impossible) for robots.

In 2013, England’s Oxford University released a study looking at which jobs would be automated to some extent in the next 20 years. NPR crunched the data and assigned probabilities to the chance of a job being automated: restaurant cooks, 96.3%; servers, 93.7%; tour guides, 90.6%; bartenders, 76.8%; head chefs, 10.1%; makeup artists, 1.0%

“I’m trying to participate to make sure, as the jobs shift, that Nevada is part of the job-creation side of that and not just the job-loss side,” said Steve Hill, who runs the Governor’s Office of Economic Development. He thinks job opportunities tied to adopting robotics could range from machine maintenance to design. He emphasized the importance of workforce training and helping UNLV serve as an incubator for new products.

Oh sees that kind of investment paying off for the state in waves. “Nevada needs a ‘brain gain’ versus a ‘brain drain.’ We need to keep our best and brightest students and workers to grow the high-tech industry and elevate quality of life, our educational system and work skills.”

Officials with the Culinary Union, which represents about 57,000 Nevada workers, also stressed the importance of job training when asked about scenarios where robots might fill lower-skilled jobs. Any new tech that could impinge on workers would be discussed during contract negotiations, said spokeswoman Bethany Khan. “Our priorities are the same as they have been for over 80 years: to ensure that Nevadans have a good job.”

Recognizing that automation could alter the hospitality workforce, Hill says growing pains are to be expected.

“I don’t know that the pushback is necessarily coming from the companies,” he said. “But it is disruptive. There is (desire), I think, on the part of everyone involved, to minimize the pain that comes from that disruption. ... Certainly, industries that are entrenched that might see massive change have not always been super-receptive.”

Gambling on new gambling

SirDekkaz wouldn’t be caught dead in a casino. For one, the Australian gamer can’t gamble in Nevada; he’s only 17. And he doesn’t wager with cash. Instead he partakes in skin betting, estimated to be a $7.4 billion online marketplace in which players bet on virtual items that have value in video games.

The transaction takes place solely online. Bettors wager on cosmetic items, like special weapons that can be acquired in a game, and these “skins” are backed by a cash value and exchanged on third-party websites. Skins are likened to other stand-ins for cash (casino chips, baseball cards), and e-sports enthusiasts can use them to wager on the outcome of competitive video-game matches or casino games like roulette.

How Skin Betting Works

1. A gamer plays a multiplayer game online. 2. He collects exchangeable virtual items, such as weapons, that have cosmetic value in the game. 3. He transfers those items to a third-party website. 4. He uses them to bet on e-sports, pro-sports teams or games like roulette. 5. The virtual items are used as chips that have cash value. 6. Skins can then be exchanged or sold for cash.

Examples of skins, taken from Counter-Strike: Global Offensive: StatTrak Desert Eagle — a blue pistol with good long-range accuracy, valued at $26.81 (as of July 8, 7 a.m.); Autotronic Bayonet — a bayonet that has been anodized red and uses steel mesh, valued at $231.76 (as of July 7, 10 p.m.)

It might sound small, but that $7.4 billion is almost double the $4.2 billion handle for sports betting in Nevada in 2015. SirDekkaz said the most he had won from a single skin bet was $2,790, and the most he had lost on a single bet was $450.

“(I) am not personally interested in gambling at a casino,” SirDekkaz, who asked to be identified by his handle, said.

The statement embodies the millennial problem casino operators are facing. In the hope of drawing the elusive demographic, Wynn Resorts and Las Vegas Sands have opened luxury lounges, like Encore Player’s Club and Lavo Casino Club, that fuse gaming with a nightclub-like atmosphere. MGM Resorts is launching a mobile casino platform this week that will allow visitors to play slots and in bingo tournaments while they are off the casino floor. E-sports appears to be trending.

In this May 11, 2014, photo, fans watch the opening ceremony of the "League of Legends" season four World Championship Final between South Korea and China's Royal Club in Paris. Around the world, fans gather en masse to watch video game players compete in high-stakes tournaments. Fans also bet on the outcomes.

That latter industry has engaged avid gamers around the world in tournament battles often streamed live, though matches can be played in front of a live audience of thousands — broadcast on arena screens and sharing the appeal of attending traditional sporting events.

The trend has digital and physical footprints, including in Las Vegas. It taps into the way millennials like SirDekkaz like to gamble — through immersive games that rely not just on chance but also skill. So what is a casino, filled with slots and table games, to do? Chris Grove, an industry analyst at Narus Advisors, believes there are clues embedded in how e-sports and skin betting operate.

“They really provide a roadmap for the Las Vegas casino industry to follow if they want to engage that demographic,” Grove said, noting that millennials might seek to bet on virtual items, like skins in video games, that are more disconnected from cash than slot-machine credits.

In a recent survey of gaming-industry stakeholders conducted by Grove’s firm and consultant Eilers & Krejcik Gaming, 82 percent of respondents said they believed casinos should host e-sports events, but only 49 percent had devoted resources to it. This leads Grove to believe the industry is hesitant to dive full-tilt into the technology.

But there are examples bucking that trend in Las Vegas. In addition to a Beijing-based firm expressing interest in building an e-sports arena here, MGM Resorts International hosted an e-sports championship in the spring. And the Downtown Grand continues to be a prominent booster, through its e-sports lounge, residency opportunities for teams and events that support the phenomenon. In a Las Vegas Weekly story about a viewing party for a massive tournament last year, Seth Schorr, CEO of Downtown Grand owner Fifth Street Gaming, said: “It’s our desire at the Downtown Grand to become the premiere video game and e-sports destination, which is really something that doesn’t exist today — a 365-days-a-year destination for video game enthusiasts.”

Schorr believes e-sports betting could make gaming more compelling for younger players. In another interview, he asked, “Is it a problem today that millennials are not gambling? The problem is what’s going to happen five or 10 years from now. Are the products relevant to a new generation?”

This is the question casinos must answer, weighing the risks and benefits of change. The market for e-sports betting is largely unregulated, and some say it could compromise the integrity of games, though Nevada regulators are exploring it. “We are in the beginning stages of looking at it and understanding exactly what it means,” said A.G. Burnett, chairman of the Nevada Gaming Control Board.

While this trend doesn’t appear to be generating much pushback, an older form of online gambling has been a recurring flashpoint for the Strip.

Off the table and into the frying pan

When it comes to online gaming in the U.S. — poker played through an app or laptop — there is one consistent opponent: Las Vegas Sands Corp. Chairman Sheldon Adelson.

Many have suggested that Adelson sees it as a threat to his business. But company spokesman Ron Reese rejects the claim. He mentioned Adelson’s security concerns and belief that the barrier to gambling shouldn’t be as easy as whipping out a smartphone. “People gambling at their kitchen table is not a scenario he likes,” Reese said.

The Effort to End Online Gaming

In 2014, the U.S. Senate introduced a bill called the “Restoration of America’s Wire Act” to end online gambling. Divisions at the time reveal where the Strip might stand as such efforts continue. The legislation was reintroduced in the Senate last year but has languished.

This puts Adelson at odds with some of the Strip’s power base. Through a subsidiary, Caesars Entertainment offers online gaming in Nevada with its World Series of Poker platform, and MGM Resorts is poised to jump in once it takes full ownership of Atlantic City’s Borgata, which has existing online-gaming infrastructure.

The market for online gaming is nowhere near what it was in the unregulated heyday of the early 2000s. A patchwork of states allow it, including New Jersey, where casino games are legal. In Nevada, there’s only poker. That may be one explanation for the lackluster performance of online poker since it was legalized in 2013, with just two licensed websites and a market too small to warrant reporting by gaming regulators.

When it was reported, online poker’s take in Nevada surpassed $1 million once, in June 2014, a sliver of the nearly $1 billion in traditional gaming revenue that month. Station Casinos tried online gaming but halted operations in 2014 after it failed to meet projections.

Yet some executives and state officials seem to see opportunities for Nevada in the expansion of online gaming. At a recent panel convened by Gov. Brian Sandoval to discuss emerging gaming tech, a Caesars VP suggested legalizing more casino games in the platform. And Sandoval expressed interest in signing an interstate agreement with New Jersey to broaden the pool of people playing here.

If it takes off, opponents worry it will erode the physical casino model. Consumers, the argument goes, might not come to a casino if they can get their fix online. But at a recent meeting of the Gaming Policy Committee, top Caesars executive Michael Cohen and MGM Resorts’ Murren brushed off concerns. If anything, Cohen said, it had helped attract millennials and spark their interest in the traditional casino.

“I don’t think 20 years from now there is any less gaming online,” said Bo Bernhard, director of UNLV’s International Gaming Institute. As he points out, this is not the first “threat” to Las Vegas’ gaming establishment. There was Atlantic City, tribal casinos and Macau. He argues that some of these threats turned out to be benefits: “Growth elsewhere has often meant growth in Las Vegas.”

The real disruption will be tied to who has the knowledge and wherewithal to offer the best online-gaming product.

“The current distribution of winners and losers will likely shift,” Grove said.

“The next thing”

Whatever is on the tech horizon, Las Vegas is counting on the same thing it always has: the social impulse.

“A great front-desk worker wants you to have a good time,” Rippee said. “A great concierge cares that it’s your honeymoon.”

That connection is just as important to the hospitality leaders embracing new technology. Downtown casino mogul Derek Stevens is among them. He co-owns several Fremont Street properties with his brother Greg, including the D. In 2014, it started accepting virtual currency bitcoin in limited capacities, and the property recently hosted an event that integrated Periscope, a live-streaming app Derek Stevens is particularly fond of. In December, the downtown casino will host an e-sports tournament. Stevens said these offerings helped grow the business, and that he didn’t see any downside.

Tourism defines Las Vegas’ economy and identity, meaning consumers must see it as a destination always offering something relevant. Which is why, for the most part, there hasn’t been that much resistance to new technology. If anything, the core industries are zealous in trying to make new tech fit regulations and the current model. There are powerful incentives to adapt.

“I think in Las Vegas,” Stevens said, “everybody is trying to figure out the next thing.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy