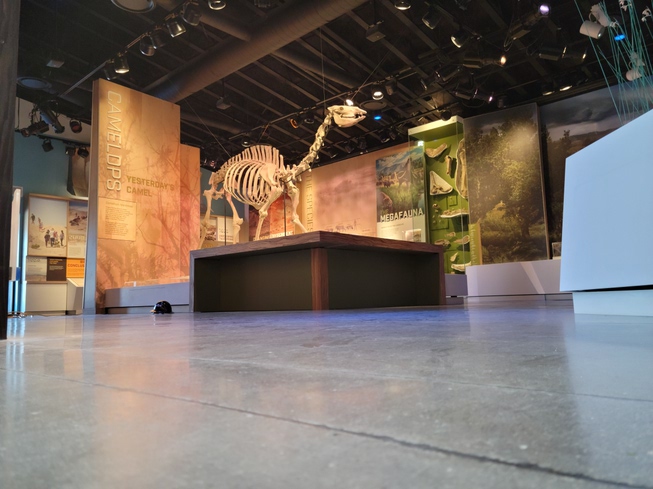

Courtesy of Nevada Division of State Parks

The visitors center at the Ice Age Fossils State Park features this skeletal display of a camelops, sometimes known as “yesterday’s camel.” Ice Age Fossils State Park, the Nevada Division of State Parks’ newest venue, will open to the public Jan. 20 at 8660 N. Decatur Blvd.

Wednesday, Jan. 10, 2024 | 2 a.m.

Before Ice Age Fossils State Park had a name, Dawn Reynoso and her UNLV classmates would dig for 25,000-year-old fossils there.

In 2011, she and other geoscience undergraduates would lay on their stomachs, brushing dirt off of fossil fragments with paintbrushes and talking about how incredible it would be to find something museum-worthy.

The 3-foot tall mammoth tusk they uncovered that summer will soon be on display at the new park’s visitor center.

The 315-acre park, southeast of Tule Springs Fossil Beds National Monument, will open Jan. 20. And Reynoso will be the park’s head interpretive ranger.

The park, at 8660 N. Decatur Blvd., will charge $3 for entry.

The Nevada Division of State Parks first announced the $12 million project in 2017.

Some 25,000 years ago, the area was home to a spring and marshland. It sustained Columbian mammoths, camelops (or yesterday’s camels), dire wolves, lions, and ancient species of bison, horses and ground sloths traipsed there.

There is an abundance of fossils at the park and a history of excavations that Reynoso hopes to continue.

“With so many fossils out here and so much we have to learn, it’s a great opportunity for students,” Reynoso said. “I would like to pay it forward.”

Graduate and doctoral students have worked on projects at the site, usually funded by research grants filed by UNLV faculty. Reynoso said those projects were active until the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Once the park is more established, UNLV’s geoscience department could organize digs at the site once again.

Recently, Reynoso started working with UNLV professors to apply for National Science Foundation grants to bring in local school teachers for hands-on science lessons at the park.

Eventually, Reynoso said, she hopes to bring high school science classes to the park to collect samples for radiometric dating.

She led a group of high schoolers for a similar project in 2010 at Valley of Fire State Park northeast of Las Vegas.

“We’re trying to get them involved in real research … trying to expose them to different things,” Reynoso said.

Their plans hinge on how busy the park gets once it opens and how well the small staff can meet the demand, she said. “We’re anticipating we’re going to be busy,” she said.

The visitor center will be home to more than just a gift shop. Guests will be able to look at displays covering the area’s natural history and the history of excavations at the site.

The Tule Springs Expedition, also called the Big Dig, ran from 1962 to 1963. It revealed that humans and large mammals of the Pleistocene era, which lasted from about 2.58 million to 11,700 years ago, never coexisted in the area.

Touch screens will let visitors piece together bone fragments and identify fossils, get a high-resolution look at the fossils on display and scroll through photos from the Big Dig. A theater will run a film about the park’s history.

Every rainfall exposes more fossil fragments at the park, providing the opportunity to add more specimens to the park’s collection.

That’s how the camel teeth that will be on display at the visitor center, found about two years ago, got there.

Tyler Kerver, a spokesman for the Nevada Division of State Parks, said the park had four trails, totaling about 4 miles. That includes the Megafauna Trail — a 0.3-mile trail featuring metal sculptures of historic megafauna found on the site. Megafauna are large animals weighing more than 2,200 pounds.

Interpreters like Reynoso will lead guests on tours along some of the trails.

One of the trails runs past the Monumental Mammoth, a towering art piece built by two artists out of discarded metal collected by volunteers at Tule Springs Fossil Beds National Monument.