Hillary Clinton poses for a photo with her Nevada staff after a news conference in a parking lot on her way out of town after her Nevada Democratic caucus win Saturday.

Sunday, Jan. 20, 2008 | 2 a.m.

Five reasons behind Sen. Hillary Clinton's victory in Nevada:

- Foresaw a huge wave of new voters unlike in her failed Iowa campaign.

- Worked relentlessly to appeal to Hispanics from the ground up rather than the top down.

- Sewed up the support of many Culinary workers long before the union endorsed Obama.

- Dominated among women and then persuaded them show up to caucus.

- Won the final week of publicity with tough political gamesmanship.

2008 Caucus Coverage

- How Clinton hit pay dirt

- The people have spoken

- Breathless: Last Hours

- Culinary Union can’t muscle win

- Turnout looks good to Romney

- Ralston: Struck by caucus firsts

- Reid keeps choice a mystery

- Big numbers are nice a problem

- Switch fattens Dems’ numbers

- Video: Culinary and The Caucus

- Video: Caucus confusion

- Video: Romney wins GOP

- Photo Gallery: Caucus 2008

- Panorama: Caucus in Paris

- Interactive: Voices of the voters

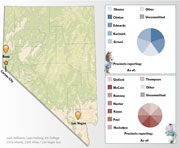

- Interactive: Caucus Results Map

- The Voting Breakdown

If you want to know how Sen. Hillary Clinton won a convincing victory in Saturday’s Nevada caucus, look back to a meeting Dec. 15 at William E. Orr Middle School in Las Vegas.

There, Robby Mook, Clinton’s state director, told 600 of the campaign’s most committed volunteers that he wanted to enlist many more supporters to caucus for the candidate -- more than twice what he asked for in August.

It was a startling move coming nearly a year into the Nevada campaign -- and just five weeks before the caucus. It also was a strategic risk because it would divert resources.

Mook’s colleagues in Clinton’s Iowa campaign paid no attention to his move. Turns out, they should have.

Clinton’s Iowa team would be blindsided three weeks later by a big turnout that favored Illinois Sen. Barack Obama. The Clinton team there hadn’t thought to consider Obama might draw out many voters who normally don’t participate in elections.

In Nevada, Mook looked at the landscape and found the following: Democrats, despite the predictions of naysayers, had taken a real interest in the presidential caucus. He feared that the campaign would fail if it limited itself to rounding up support only from voters with a history of participation.

So as he spoke to volunteers that cold December Saturday, Mook’s usual confidence was clearly shaken. Clinton needed to mine the electorate for voters the campaign originally thought would not participate.

It was a tall order. Campaigns have an easier time if they can work from lists of “likely voters.”

“We need to work hard now,” Mook told the group. “If the caucus were held today, we’d do OK. We would not be as successful as we want to be.”

The Sun was given access to the Clinton meeting, as well as to other internal discussions by the Clinton campaign, while also conducting background interviews with Obama staff, under the condition the paper not publish any of what it learned about strategy until after the caucus.

Mook said in an interview Saturday that his staff groaned at the suggestion of expanding the universe of voters, especially to such a radical new goal: Find 60,000 more. Some analysts estimated that was as much as the entire expected turnout statewide. (In August, the Clinton goal was 24,752 supporters.)

Now, not only was Mook pushing for an unheard-of total, he was also brutally honest about the profile of the average Clinton voter at the precinct captain meeting: Clinton supporters “are less likely to turn out,” he said. “They don’t understand the caucus.”

Reaching the new number required immense amounts of motivation, both of the voters and the volunteers trying to reach them.

The motivation came from the campaign and its best surrogates.

The endorsement of Clark County Commission Chairman Rory Reid was always seen as a good early “get,” but the campaign never expected him to go to the lengths he did.

At precinct captain meetings in August and December, Reid, not known as much of an orator, fired up the troops. His work and commitment made the sale authentic.

“I want you to feel the urgency of what’s going on here,” he said in December before closing with a “Field of Dreams” cliche: “If you do it, she will win.”

Mook played bad cop at the December meeting. He laid out what he expected from volunteers: hard-core supporters about whom the campaign would have no doubts, one volunteer for every 10 supporters, and a pledge to canvass the neighborhood twice a week, work the phones and host parties. No wavering supporters.

Five weeks later -- on Saturday -- Mook’s team hit the number, and the staff members were thanking Mook left and right for giving them the bigger goal, he said.

The Nevada caucus turned Iowa on its head. There, Clinton hit her original goal but was deluged by the Obama turnout. Here, the turnout was nearly double the 60,000 forecast -- standing at 115,800 late Saturday with 2 percent of precincts yet to report.

One precinct in a middle-class Las Vegas neighborhood showed the success of Clinton’s effort.

State Sen. Steven Horsford, a supporter of Obama, said the vote goal in his precinct was 29. Obama surpassed it easily with 45.

Clinton had 58.

Mook credited the Clinton precinct captains: “I give a lot of credit to our precinct captains. We came out of Iowa, and we never felt like we were losing them. People had a personal relationship with the campaign.”

Those precinct captains had to adjust midstream to an influx of voters no one expected. But because the campaign found them and nailed down their commitment, they were ready to take on the new goal.

Mook had set the much higher target because he was picking up signs of increased interest in the caucus.

The signs were clear to anyone watching: Democrats eager, even desperate to take back the White House, running a strong roster of candidates with talented field organizers. And December polling in Iowa and New Hampshire showed close races.

But not everyone was so savvy. The campaign of former Sen. John Edwards, for instance, was using a turnout model of 45,000 total voters, according to a campaign official.

Aside from heavy turnout, the Clinton camp made another smart strategic move that was aided and abetted by a strategic blunder: Although the Clinton team won’t admit it publicly, the campaign had been working Culinary Union members hard and organizing them for the past year. The effort recognized that because the union was waiting so long to make an endorsement decision (it didn’t come until 10 days ago), the campaign could peel off members and get them committed and working while the union dithered. The result was a surprising victory at seven of the nine special Strip caucus sites.

Most remarkable about this organizational drive is that it required secrecy -- if the Culinary found out, the union would have worked to shut it down.

And even though Clinton fared well at the Strip sites, she also benefited from the lawsuit filed to have the sites closed, according to interviews with voters, who expressed anger that Culinary workers -- and by extension, Obama -- were given disproportionate influence in the total delegate count because of the at-large sites.

The claim about delegate allocation wasn’t true, but many voters believed it to be so, which is all that mattered.

The Culinary is 49 percent Hispanic, and Clinton dominated among Hispanics statewide, according to exit polling.

Although the Clinton victory was decisive, especially with women, her victory among Hispanics was especially striking, beating Obama 2-1 with a demographic that comprised 15 percent of the voters, according to exit polls.

This was evident in Clinton’s campaigning the past 10 days, when she aggressively courted Hispanics and hit the issues they cared about. Lately, that means the economy and the mortgage foreclosure crisis, which is hurting working-class Hispanics especially.

“We refused to take it for granted and worked very, very hard knocking on doors multiple times,” Mook said. “We focused on the doors.”

To be sure, the Clinton organization wasn’t always a well-oiled machine. At a December meeting called to create a caucus-training guide for volunteers, the staff wrangled over verb choices and what color marker they should use.

For Clinton’s team, no doubt Obama’s Iowa victory drew the challenge into clear relief.

For their part, Obama’s supporters said the loss was a moral victory, given that they started from nothing a year ago and were going against much of the party establishment, save the Culinary.

“We made up 25 or 30 points in two months; things are going our way,” said Billy Vassiliadis, an Obama adviser and the chief executive of R&R Partners, an advertising and public affairs firm.

Vassiliadis acknowledged Obama and his campaign must do better with Hispanics to succeed in states such as California.

The Obama team points out that he could actually walk away with more delegates to the national convention than Clinton because he won in some rural counties that are given more weight than Clark County, where Clinton won handily.

But that won’t cloud the fact that this was a hard-fought victory for Clinton, one that seemed certain six months ago but extremely uncertain a week ago.

It’s not clear whether there was any impact from late advertising and media attacks on Obama’s record on abortion, the nuclear repository at Yucca Mountain or his alleged lack of support for gaming.

And though it’s easy to slice and dice and analyze strategy, there’s this: Nevadan Democrats put their faith in Clinton and her experience.

At dozens of precinct locations voters interviewed by the Sun cited Clinton’s experience as the overriding factor in their decision.

As Mook said, “Sen. Clinton spent a lot of time here, and her presence here was more substantive and focused more on issues. (The voters) decided it was not a popularity contest.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy