AP

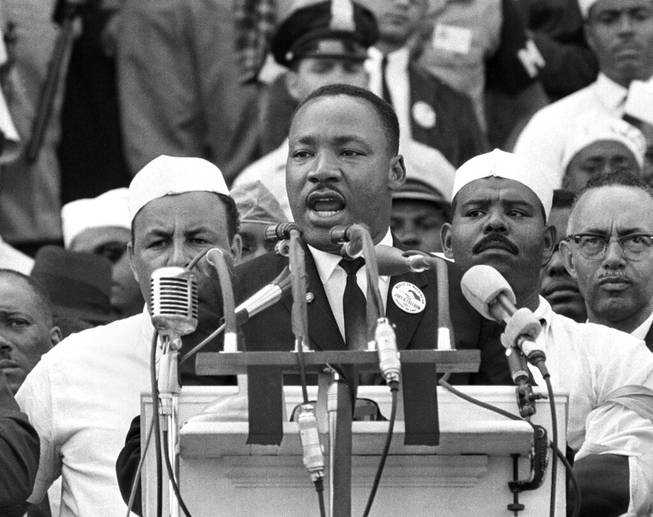

In this Aug. 28, 1963, file photo, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, addresses marchers during his “I Have a Dream” speech at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington.

Monday, Jan. 15, 2024 | 2 a.m.

View more of the Sun's opinion section

The 2024 presidential party nominating process officially kicks off today with the Iowa Republican caucuses. It is also Martin Luther King Jr. Day in the United States, an annual day of service and reflection on the life and legacy of one the most influential civil rights icons of the 20th century.

For many Americans, that legacy starts (and too often ends) with King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial during the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

But while King’s dream has inspired generations of Americans to stand up for justice and equality, his life and legacy are about far more than a dream for future generations.

He demanded that the United States fulfill the promise of dignity, opportunity and equality under the law for all people, regardless of the color of their skin or the amount of money in their bank accounts. These should not have been radical demands and yet well-intentioned people, including some who claimed to be King’s allies, repeatedly accused him of being too radical, too aggressive and too impatient.

One of those critiques came in April 1963, when King sat alone in a Birmingham, Ala., jail cell, far from the cheering crowd he would inspire four months later.

King had been arrested after organizing a peaceful civil rights march through a downtown shopping district and business corridor in Birmingham. He was charged, along with Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) activist Ralph Abernathy and Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (ACHMR) and SCLC official Fred Shuttlesworth, for violating what was undoubtedly an unconstitutional injunction against “parading, demonstrating, boycotting, trespassing and picketing.” His request for a permit had been denied by Bull Connor, the openly racist commissioner of public safety in Birmingham.

While in jail, a local newspaper published a letter by eight white clergy members entitled “A Call for Unity.” The letter offered sympathy for King’s goals but described King as “an outside agitator” who had no business leading protests in Birmingham.

It called on Black Americans to be patient and to wait, just a little bit longer for the promise of dignity and freedom to be fulfilled.

For the man sitting alone in a Birmingham jail for little more than existing with other Black people on a Birmingham street, the letter struck a nerve.

Using the margins of the newspaper, scraps of paper provided by other inmates and, eventually, a legal pad provided by his attorney, King drafted a 7,000-word response King referred to as “Why We Can’t Wait.” It is now known as the “Letter from Birmingham Jail.”

In it, King writes directly to his critics, condemning their selfish tribalism that pits neighbors against neighbors instead of honoring the shared humanity of all people and the shared goals of peace, prosperity and freedom.

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere,” he wrote. “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly,” he continued. “Never again can we afford to live with the narrow, provincial ‘outside agitator’ idea. Anyone who lives inside the United States can never be considered an outsider anywhere within its bounds.”

He then critiques the narrow-minded ignorance and silence of his critics, noting their willingness to sit on the sidelines through decades of injustice, only to speak up when it was socially and politically convenient. “You deplore the demonstrations that are presently taking place in Birmingham,” noted King. “But I am sorry that your statement did not express a similar concern for the conditions that brought the demonstrations into being.”

Finally, with regard to breaking the law, King explained that there are two types of laws: just and unjust. “Any law that uplifts human personality is just,” said King. “Any law that degrades human personality is unjust.”

Which brings us back to today’s caucuses in Iowa and the 2024 election cycle that is now upon us.

Imagine if voters elected leaders who valued Dr. King’s values of nonviolence and equality instead of valuing alliances with militant white nationalists.

Imagine if voters elected leaders who believed in the shared humanity of all people and the shared goals of peace, prosperity and freedom, instead of seeing immigrants, LGBTQ+ people and others as outsiders unworthy of human dignity and opportunity.

Imagine if voters elected leaders who believed in learning about history — the good, the bad and the unimaginably awful — without feeling guilty or ashamed because they have the wisdom that history can’t be undone, it has already occurred, and only by learning from it can we hope to make tomorrow better.

And imagine if voters elected leaders who asked whether their policy proposals “uplift human personality” or “degrade human personality.”

Realizing Dr. King’s dream will not occur until we elect leaders and lawmakers who share his values and implement them even in the loneliest of places.

It will not happen until voters and our elected leaders care about injustice anywhere and try our best to do the right thing, even in places where there are no cameras, no stage and no crowd. Even if the only person who sees it is one man, sitting alone in a prison cell with a dream for humanity.