The El Paso - Limousine Express pulls away from a downtown bus station. The manager at this station estimates that 100 people a week are buying one-way tickets to Mexico. They’re going home because they can’t find work building homes in the Las Vegas Valley.

Sunday, April 6, 2008 | 2 a.m.

Housing Slump

The housing slump in Las Vegas, now in its second year, has affected thousands of Hispanic construction workers who have left the city as their jobs disappeared. Most of them are undocumented illegal immigrants, so the government has little information on them. However, their departure, and the slowdown in work for those who remained, is causing a corresponding slump in businesses that cater to them, including grocery stores and apartments.

Alejandro Salazar slumps into a cushioned seat halfway into the bus, looks out from under a baseball cap and thinks about a future more than a thousand miles away. He came to the Las Vegas Valley from Mexico five years ago to build houses, launching a run of $700-a-week paychecks that made it worth crossing the desert into the United States. But those weekly checks were whittled down to $200 over the past year; he sold his van and is returning to Aguascalientes. “At least I have family there,” he says, shrugging his shoulders.

He has $60 in his jeans pocket. A friend stuffed the money into Salazar’s hand just before he climbed onto the bus at the Charleston Boulevard and Eastern Avenue station.

Salazar is among unknown thousands of Hispanic construction workers who have left Las Vegas as their jobs evaporated in the homebuilding slump, now in its second year. Thousands more are still here but earning much less than they did even a year ago.

The combined effect is hitting companies that cater to Hispanics especially hard. Supermarkets, apartments and other businesses report unprecedented declines in revenue. Those businesses, in turn, are laying off workers or cutting back their hours.

Just how many construction workers are affected is impossible to know. Most of the people leaving are illegal immigrants who live under the radar of the official agencies that count heads and chart migration. The same is true of those who remain.

Nonetheless, interviews with dozens of people in residential construction and a review of state statistics on jobs in that sector suggest that at least 80,000 Hispanic immigrants are struggling economically or have left the state.

The math:

• Nearly 100 percent of the workers who build homes in the Las Vegas Valley are Hispanic, and most of their families include illegal immigrants. An estimated 60 percent to 80 percent of those workers are undocumented, industry insiders say.

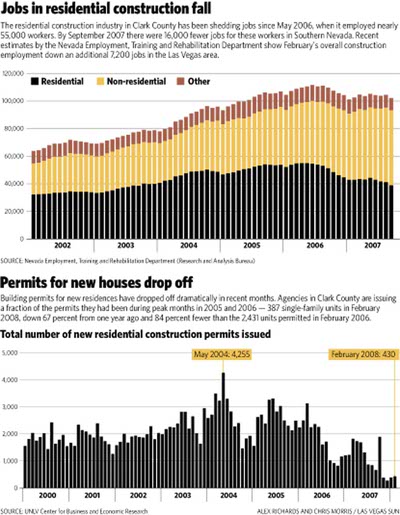

• At least 20,000 jobs in residential construction have vanished during the slump. (That figure is from a Sun analysis of state Employment, Training and Rehabilitation Department data, based on numbers provided by construction companies. The state can only assume those companies are counting jobs once held by illegal immigrants.)

• The U.S. Census Bureau estimates the average size of Hispanic families in Nevada is four.

Many of these workers and their families have fled Nevada, for Mexico or for other states. Others are hanging on here, spending less to ride out the bad times.

Many point to tightened immigration laws as an additional factor in deciding how long they will stay.

Rakesh Kochhar, associate director of research at the Pew Hispanic Center, a Washington-based think tank, says the factors at work in the Las Vegas Valley — a slumping economy coupled with a clamor for tightened immigration policies — is being seen nationwide. At the same time, the valley depends on illegal immigrants for construction more than many other areas, Kochhar says. Their departure creates an “unusual social experiment,” he says. “When in our history can we think of saying goodbye to scores of thousands of people like this?”

•••

Thirty-year-old Pascual Martinez, from Hidalgo, Mexico, has been working as a roofer since he was 18. In a trailer behind the Amistad Cristiana church on Stewart Avenue, he rubs tar off his hands while describing his family’s spiral downward during the past 16 months.

He once worked 54 hours a week. He now gets by on 15. His weekly checks have gone from $800 to $200. Martinez has a wife and three children. The youngest is 18 months old.

Sitting nearby, pastor Joel Menchaca explains that he has let the family move into a trailer the church owns for $300 a month.

It is Thursday night, and the family has eaten rice and beans every day this week. Martinez’s oldest son, 6-year-old Eric, asked for milk with his cereal this morning. There was none.

“We’re living like we did in Mexico, just surviving,” Martinez says.

He borrowed $700 from his employer a year ago; he has yet to pay the money back.

Eric asks him for remote-controlled toys and he has to tell the boy that things are hard right now. Eric sees his dad at home in the afternoon and asks why he’s not at work.

Martinez has four brothers who work in construction, all in the same situation. He says at least 10 of his friends have left Las Vegas, four of them bound for Mexico.

“I would do the same, but I think of my children and their education,” Martinez said. He thinks of Eric, who has told him, “I want to learn English and then teach it to you.”

•••

At the Broncos money order store on Desert Inn Road near Eastern Avenue, the floor on a Friday afternoon scuffs underfoot in the dust left behind by the boots of construction workers. Owner Reveriano Orozco says business at his three stores has suffered for 16 months, going from 19,500 transactions in October 2006 to 12,400 in February. His payroll has dropped from 40 employees to 25. He has sold three other stores and is about to do the same with the last three.

Ruben Martinez cashes a paycheck and sends $300 to his family in Hidalgo. That’s about half the 29-year-old stucco worker’s monthly income — so he sends money home only every other month.

At Mariana’s Supermarket on Eastern Avenue near Bonanza Road, store manager Fernando Nuno says business is down 15 percent in the past eight months, the sharpest drop in sales since the chain of four stores opened in 1986.

Nuno says the company has cut back hours worked by its 500 employees by about 15 percent. Two other chains of four supermarkets report declines in sales of at least 10 percent. One has cut back hours for 220 employees.

At Cedar Arms apartments, off Eastern Avenue a few blocks south of Mariana’s Supermarket, 12 of 80 units are vacant, the most manager Alex Miranda has seen in four years on the job. Some families went to Mexico. Others left for neighboring states. Rent has dropped $50 for each apartment, to $525 for a one-bedroom.

Not surprisingly, ZIP codes with large Hispanic populations, including 89030, 89115 and 89104, are experiencing high vacancy rates. The rates there have ranged from 10 percent to 14 percent during the past six months, compared with 8 percent to 9 percent for the entire valley, according to CB Richard Ellis, a real estate services company.

At Club Barajas on West Charleston Boulevard near Decatur Boulevard, a man at the bar is willing to talk but won’t give his name because he has laid off more than 50 workers, including family and friends.

His eyes have an empty look. He says he stays up nights, turning over the names of his new enemies, the ones he cut off from their livelihoods.

“You fire your cousin or you fire your friend,” he says. He pulls on his third Corona. “You play Russian roulette. My wife says, ‘Do what you have to do.’ ”

He names three companies he has worked with during five years of supervising homebuilding crews. Two laid off 400 workers each. The third cut 565, he says.

Jonathan Iniguez, the bar’s manager, says he used to cash the paychecks of workers, dozens of whom would surround the pool table and dance to mariachis. That all stopped about six months ago.

Liquor sales are a third of what they were, and poker machines bring in one-fourth as much. The seven mariachi musicians, each of whom pulled in up to $300 for four hours of brassy partying, don’t come around anymore. Iniguez has laid off two of six bartenders.

That’s what happens in a slumping economy, says Keith Schwer, director of the UNLV Center for Business and Economic Research. “If you take out spending in the economy, you’re going to take out more than initial spending ... (and) in general, one job lost takes another with it.”

•••

Nearly 10,000 construction workers filed unemployment claims statewide in February. Illegal immigrants don’t qualify for those benefits, or for welfare or food stamps. Many have turned to churches for help.

Menchaca, president of a group of 80 Christian Hispanic churches, says some pastors are seeking help from church-based projects that sell food at reduced cost. Others are letting their parishioners live on church-owned property.

At Ebenezer Christian Church, in a storefront at an East Las Vegas mall, pastor Ciro Solano preaches on a Friday night that “the Word is for the poor as well as the rich.” Fifteen or more of Solano’s 50 parishioners have been affected by the downturn, he says.

Parishioner Pedro Godinez says he has been reduced to working 30 hours a week, the least in his 13 years as a house framer. But he’s better off than most of his friends: Three have lost homes and two moved to California.

Godinez and many other workers interviewed for this story say the shrinking residential construction industry is only partly to blame for their plight. They mention state and federal laws making it harder for employers to hire illegal immigrants.

The 2007 Nevada Legislature passed AB 383, which gave the Taxation Department the authority to fine employers the federal government determines have knowingly hired workers with false Social Security numbers.

In March, six months after the law took effect, the attorney general decided that existing federal law trumped and invalidated the state law. But that kind of information filters slowly down to street level, especially in the Hispanic immigrant community.

Benjamin Powell, research fellow at the Independent Institute, a Washington-based think tank, says the combination of worker exodus and tightened immigration laws could create problems for Southern Nevada’s economy down the road.

“When things turn around and there’s a boom, you’ll be constrained on labor, so Las Vegas won’t be able to expand as it has,” he says.

Jeremy Aguero, principal analyst at the Las Vegas company Applied Analysis, says the exodus “creates not only a problem for today, with a decrease in spending, but in the future, when it will be more difficult to ramp up the economy.”

One problem is the difficulty illegal immigrants who have gone back to Mexico might have in entering the country again. With a wall going up along the U.S.-Mexico border and calls for the federal government to crack down on illegal immigration, it seems likely that getting back into the United States will be harder.

•••

Salazar sits on the bus, that $60 tucked in his pocket, headed to Aguascalientes.

Erika Chavira, manager at the bus station, says about half her passengers have been buying one-way tickets to Mexico in recent months.

Bus driver Antonio Padilla says he hasn’t seen anything like it in 24 years behind the wheel.

Many travelers are heading home because there is no work. Some carry tools onboard. Chavira estimates that 100 people return to Mexico each week on her buses, or more than 5,000 a year.

Outside are the three friends who came to say goodbye. They say they might soon follow.

“It’s a miracle we’re still here,” says Jose Sanchez. “We’re on a tightrope.”

Jose Castaneda says the three are seeing how long they can hold out.

Onboard, someone asks Salazar about his future.

“Oh, I’ll be back — in about three years.”

Sun reporter Alex Richards contributed to this story.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy