Friday, June 20, 2008 | 2 a.m.

Sun Archives

- Diversity takes hit for higher academic standards (7-16-2007)

- Q+A: David Ashley (3-18-2007)

- For UNLV, UNR, only the best and brightest (11-22-2005)

- Poll: Most Nevadans support tougher college admission standards (10-29-2005)

Beyond the Sun

Hoping to attract a more diverse student body, UNLV officials are looking to give more prominence in their school’s admissions process to measures other than grades.

Prospective students would get credit for such things as leadership skills, overcoming hardship and being the first in their families to attend college. Administrators want to consider applicants’ life circumstances when assessing their performance and potential.

“The central focus,” President David Ashley said, “is to identify and admit students most likely to succeed.”

The drafting of new standards comes nearly two years after Nevada’s public universities began requiring higher grades for admission.

To get into UNLV or UNR this fall, the vast majority of students need a grade-point average of at least 3.0 in 13 high school classes in English, math, natural science and social science. In fall 2006 and 2007, applicants needed a 2.75 in those core classes. Before that, they needed only a 2.5 overall GPA.

Some higher education officials say it is unclear how the changes are affecting American Indian, black and Hispanic students, who tend to do worse than their peers in school.

But a report the Board of Regents heard early this month shows that fewer American Indian, black and Hispanic freshmen entered UNLV last fall than in fall 2005, the last year students were allowed in under the old rules. In contrast, more Asian/Pacific Islander and Caucasian freshmen enrolled last fall than in fall 2005.

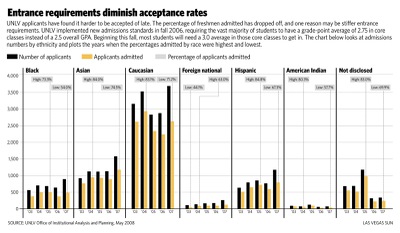

Information UNLV provided to the Sun shows steep drops in the percentages of applicants admitted from some minority groups.

The data is not ironclad; prospective students self-report their ethnicities, and between 4 percent and 17 percent did not even declare one in recent years.

Still, in fall 2005, the percentage of Hispanic applicants admitted to UNLV was higher than for any other ethnic group, at 84.8 percent. By fall 2007, it had dropped to 67.3 percent. Over the same period, the percentage of black applicants admitted fell about 20 percentage points, to 54 percent, and so did the percentage of American Indian applicants admitted, at 57.7 percent.

The proportion of Asians and whites admitted dropped as well, but by fewer percentage points.

Such trends worry educators who want UNLV’s student population to look more like that of Clark County, which the American Community Survey estimated was 9.4 percent black and 27.2 percent Hispanic in 2006.

In fall 2007, 8.6 percent of UNLV’s undergraduates were black and 12.9 percent were Hispanic. Last fall’s freshman class was 7.7 percent black and 15.6 percent Hispanic. American Indians were slightly overrepresented.

Officials have tweaked admissions in ways they thought would benefit underrepresented groups. In 2007, regents agreed to admit more applicants using “alternate criteria,” including good performance on standardized tests, overcoming adversity, and “other special circumstances.”

This year, the number of special admittees may be as high as 15 percent of the number of freshmen accepted the previous year, up from 10 percent of the previous year’s freshman enrollment.

Last year, UNLV required students whose grades were too low to appeal for additional consideration. This year, the school has changed its process, automatically evaluating applicants under alternate criteria if they miss the GPA mark. The new, “holistic” admissions system UNLV is developing would not cap the number of students the school accepts using measures other than grades.

Ashley hopes to bring a proposal to regents within the next year, but said he does not yet know exactly how the new procedure would work. One option: UNLV could assign weights to criteria such as overcoming hardship or possessing artistic or musical talents, and students could gain admission by meeting enough criteria.

“I am a great believer in (the philosophy that) the campus environment, the intellectual environment, is substantially enhanced by student diversity,” Ashley said. “So I think it’s important to find ways to maintain the diversity of the campus with students who can succeed.”

He emphasized that increasing ethnic diversity was not his only objective. Economic and other types of diversity matter as well, he said.

“I look for an approach that appropriately values the intellectual capabilities, experiences and accomplishments of the individual without specifically including race or ethnicity as a criterion,” he said.

Still, at least one member of his Cabinet thinks taking race into account in admissions would be an appropriate way to increase diversity — if only Nevadans were ready for that.

“I would like for us to consider race, but I do not think there is support for that in Nevada at the moment,” said Christine Clark, vice president for diversity and inclusion at UNLV. “People do not yet understand the educational benefits of diversity for all students ... We have some education to do to open people up to the value of including this as one of many factors in our evolving admissions process. In the interim, we will use some of the other factors to accomplish the same ends.”

How much holistic admissions will contribute to diversity depends on what system UNLV chooses and how the school implements it. Activists have slammed California’s elite universities for enrolling too few underrepresented minorities despite using admissions criteria similar to those UNLV is considering.

Ashley imagines that even under a holistic admissions system, UNLV would continue accepting all applicants with a 3.0 GPA. That leads some skeptics to question how different any new process would be from the current one, given the existing allowance for alternate admissions.

“Saying a 3.0 gets you an automatic admit is another way of saying it’s not really altogether a holistic approach,” said Gary Peck, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Nevada.

Such a system still places too much emphasis on grades while neglecting other factors that could better indicate how well a student will do in college, he said.

Other critics have a very different concern.

Terence Pell, president of the Center for Individual Rights, a nonprofit law firm, said states should not judge people by their skin color, and holistic admission procedures that rely on vague or subjective criteria are often “used as a proxy for race.”

“At some schools, it’s the case that minority students overwhelmingly are shunted through this kind of alternative,” he said.

“If it turns out that students from nonminority races benefit from the alternative criteria, and it turns out that the degree of preference given ... isn’t that significant, then there’s no real issue,” Pell said.

As of early this month, 15.8 percent of undergraduates accepted using alternate criteria were black and 19.6 percent were Hispanic. Black applicants accounted for 8.1 percent of those accepted on the basis of grades alone. Hispanics made up 14.7 percent.

Michael Wixom, regents chairman, worries that students with poor academic records will struggle at the university. Many could benefit from attending community college before transferring to UNLV, he said.

“One of the reasons that I pushed so strongly for the admission standards is that my whole feeling is that students need to be where they can succeed,” Wixom said.

Pell said students admitted under the alternate criteria are prone to failing at dramatically higher rates than classmates with better academic records. Other experts contest that view, however.

Next year, UNLV aims to ensure the success of more of the students it admits under alternate criteria by requiring, for the first time, that they obtain academic advising.

Holistic admissions systems, Ashley argues, do not lower standards but use a variety of criteria, instead of grades alone, to select the best students.

In the meantime, grade requirements are going up, and as that happens, putting more resources into outreach programs that prepare high schoolers from underrepresented groups for college is crucial, said Richard Siegel, president of the ACLU of Nevada.

UNLV has not significantly increased its investment in outreach in recent years, said Neal Smatresk, executive vice president and provost. But the school has ramped up recruiting to encourage more students, including minorities, to enroll.

Staff are making extra efforts to relay information about UNLV to students and graduates of the College of Southern Nevada, the state’s most diverse public higher education institution. Admittees unsure about attending have gotten a phone call from a recruiter.

The efforts may be paying off in some categories.

As of early this month, the number of incoming black and Hispanic freshmen was up more than 40 percent over the same time last year. The number of incoming American Indian freshmen, always small, was down, however.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy