Jim Rogers left his position last week after five years as Nevada System of Higher Education chancellor.

Sunday, July 5, 2009 | 2 a.m.

One on ONE with University System Chancellor Jim Rogers

University System Chancellor Jim Rogers is stepping down June 30, ending a five-year stint as the leader of Nevada's higher education system. News ONE's Jeff Gillan talks with Rogers about his legacy and his plans.

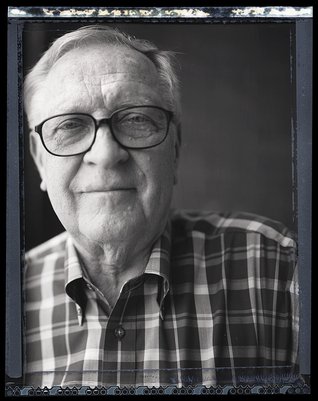

Jim Rogers (shown in a yearbook picture) started speaking his mind early, writing editorials in 1956 for the Desert Breeze, the campus newspaper of Las Vegas High School. One of his more scathing commentaries -- complaining about inequities in the school's grading system -- resulted in the principal calling his father to complain. "My father said, 'What have you done this time? They're going to throw you out of school,' " Rogers recalled. "I was 17 years old and a crusader in those days. I came from a family of Methodist ministers who were always on one crusade or another."

Timeline

- 1956: Graduates from Las Vegas High School

- 1962: Graduates from the University of Arizona with degrees in accounting and law

- 1963: Earns master of law from the University of Southern California

- 1963-1964: Teaches at the University of Illinois law school

- 1964-1987: Practices law in Las Vegas

- 1978: Acquires KVBC Channel 3, an NBC affiliate, and founds Sunbelt Communications, which operates 16 television stations in five states

- 1981-1987: Serves on the board of Nevada National Bank

- 1995: Founds Community Bank of Nevada

- 1998: Forms Nevada First Bank (now the Bank of Nevada, where Rogers serves on the board of directors)

- 1998: Donates $137 million to the University of Arizona College of Law, which is then renamed for him

- 2000: Is named one of the nation’s top 12 philanthropists by Time magazine for donating more that $200 million to nonprofit organizations, most related to education

- May 2004: Becomes interim chancellor of the Nevada System of Higher Education

- Aug. 19, 2004: Is so frustrated with the higher education system that he revokes a $25 million gift to UNLV; two months later, he changes his mind

- September 2004: In a scathing memo, tells regents that the system is dysfunctional and inefficient and that board divisiveness is largely to blame.

- February 2005: After regents give the chancellor authority to fire college presidents, says he want to be permanent chancellor.

- May 2005: Is appointed by regents as the system’s ninth chancellor.

- February 2006: In the wake of growing tensions with Rogers, UNLV President Carol Harter announces retirement.

- June 2006: His chancellor’s contract is extended through 2009 after positive public evaluation.

- January 2007: Resigns and, 36 hours later, changes his mind.

- March 2007: Alienates regents again by telling state lawmakers he would support a state constitutional amendment to have his bosses appointed instead of elected.

- April 2007: Calls for personal and corporate income taxes to help pay for education.

- August 2007: Says his family decided against making a $3 million contribution to UNR because of harsh comments regents have made about his leadership.

- May 2008: Unleashes a tirade over Nevada’s tax policy and a governor he says hasn’t returned his calls in five months.

- June 2009: Says UNLV President David Ashley should quit or be fired. Vice Chancellor Dan Klaich is appointed by regents to succeed Rogers.

— Compiled by Sun researcher Rebecca Clifford-Cruz

Sun Archives

- Regents approve new chancellor for higher education (6-18-2009)

- Rogers calls for Ashley’s ouster (6-17-2009)

- Rogers: UNLV President Ashley should be fired (6-16-2009)

- College students band together, rally against budget cuts (1-22-2009)

- Rogers adds own incentive for president (5-6-2006)

- Rogers shares wealth of experience (5-13-2005)

- TV mogul is willing to serve as chancellor (4-20-2004)

- Praises pour forth for interim chancellor (4-6-2005)

Sun Coverage

Beyond the Sun

Audio Clip

- Chancellor Jim Rogers says goodbye.

-

Ever since his high school days as a student newspaper editorial writer, Jim Rogers has risen to the occasion, inserting his strong opinions even when not invited.

This time it was in 2004.

The Nevada System of Higher Education was in disarray, confused by lack of mission, lack of money, lack of leadership. Rogers was a hardball lawyer and a no-nonsense businessman who was making money hand-over-fist as the owner of a group of television stations.

He was a legend in academia, too — for his purse if not his prowess: He made the largest donation to a law school in U.S. history and, for his gift, the school at the University of Arizona was named for him.

Throughout his career, Rogers has used everything in his arsenal — his television stations, his personal wealth, his biting wit and keen intelligence — to lecture and opine, always confident that he knew how to run things better than the other person.

In 2004 he offered to take over the helm of Nevada’s public colleges and universities. He had no prior leadership in education, save for a brief stint as a teaching fellow in legal writing at the University of Illinois. But he convinced regents that he should be given the reins. Trust me, he said. I’ll turn things around.

Five years later, he’s stepping down by his own choice, having attracted as many critics as supporters for a management style distinguished by one particular personality trait: He doesn’t suffer fools, even if they are his bosses on the Board of Regents, even if it is the governor.

Rogers’ legacy is not yet written, because he says he’s not done.

Indeed, as he walked away Wednesday from the chancellor’s office — his first destination was the family home in Montana — the 70-year-old Rogers still had a full plate.

• He will continue to campaign for his stalled pet project: a health sciences system that would link academic and research interests of the individual colleges as well as the Desert Research Institute.

• He owns Sunbelt Communications, which operates 16 television affiliates in five states, including KVBC Channel 3 in Las Vegas.

• Johns Hopkins University has invited him to teach a class at its world-renowned business school.

There is probably one job ill-suited for Rogers, says former Nevada Gov. and U.S. Sen. Richard Bryan: U.S. ambassador to the United Nations.

Diplomacy never was Rogers’ strong suit.

Bryan, who has known Rogers since their days at Las Vegas High School in the mid-1950s, said his friend’s penchant for “brutal candor” and demanding standards are part of the reason he’s been so successful as a lawyer, businessman, banker and chancellor.

“Jim Rogers is not a plain-vanilla personality,” Bryan said. “You love him, or you hate him. But everyone has an opinion.”

And for good reason.

Rogers’ highlights reel as chancellor shows impressive achievements:

• He commanded the UNLV Foundation in 2003 to raise an ambitious $500 million by 2008. It didn’t make the deadline — but is expected to by the end of this year, despite the recession.

• His relentless advocacy for higher education protected his colleges from the bone-deep cuts proposed by Gov. Jim Gibbons.

• The Boyd School of Law was named one of the top 100 programs in the nation.

But Rogers’ tenure hasn’t been without bumps and bruises.

• His clashes with UNLV President Carol Harter and UNR President John Lilley caused both to quit.

• Roger is now second-guessing his replacement for Harter, David Ashley, recommending that he be fired if he doesn’t quit first.

• He hired Richard Carpenter as president of the College of Southern Nevada and for a while stood steadfastly by him. But after questions were raised about Carpenter’s performance and he quietly negotiated for the top job at a Texas community college system, Rogers told him good riddance.

• Rogers’ infamous tirades targeting regents, campus presidents and the governor were sometimes perceived as more sideshow than substantive in his efforts to bolster higher education.

Dan Klaich, who took over Wednesday as chancellor at Rogers’ recommendation, said there’s no question that his former boss’ tactics put higher education “at the table for every major discussion. What I learned and what was reinforced working with Jim is that there’s no substitution for directness and clear, concise honesty.”

• • •

In May 2004, after then-Chancellor Jane Nichols stepped down for health reasons, Rogers volunteered his services as interim chancellor. But he wasted no time asserting his authority and making his priorities known. He banned campus presidents from hiring lobbyists for the 2005 legislative session, in favor of one systemwide lobbyist to represent their collective interests.

“Eight institutions competing for the same pile of money wasn’t helpful,” said James Dean Leavitt, the newly appointed chairman of the Board of Regents, who was elected in 2004. “One of the chancellor’s top priorities is to make sure all of the presidents are working together. In that regard, Jim Rogers has been very effective.”

Rogers also pushed for more cooperation between higher ed and the K-12 system, partnering with Clark County Schools Superintendent Walt Rulffes to reduce the remediation rate among local high school students who went on to state colleges and universities. Rogers also promised that when he sought more money for colleges, it wouldn’t come at the expense of K-12.

Rogers’ interest in running schools dates to 2000, when he volunteered his services as superintendent following the retirement of Brian Cram. Rogers’ offer was rebuffed, and Carlos Garcia was hired. When Garcia left five years later, Rogers and an elite coalition of similarly minded civic and business leaders recruited New York City Public Schools administrator Eric Nadelstern for the job, favoring an outsider’s bent for change over in-house candidate Rulffes. The group went so far as to organize a rogue mission to visit Nadelstern in New York, even as School Board members were there for their own interviews.

Nadelstern ended up pulling himself out of the running, citing concerns about working for a divided board. Rulffes, who had been chief financial officer before being named interim superintendent, was the last man standing.

Rogers now says Rulffes was the right man for the job, and Rulffes says he is grateful to Rogers for keeping the spotlight on K-12’s needs during the contentious legislative session.

“He knows that our students are higher ed’s students,” Rulffes said. “We share a common goal.”

• • •

The consensus in the inner circles of academia is that higher education improved under Rogers’ watch.

“We are more focused, we are more strategic, we are more innovative,” Leavitt says. “I think higher education has a higher profile because of who Jim Rogers is, and the message he preached.”

Rogers’ predecessor, Nichols — whom Rogers hired back to be the vice chancellor of academic and student affairs — was even more effusive. She said Rogers will “go down in history as one of Nevada’s best and strongest chancellors ever,” in part because he raised Nevadans’ consciousness of higher education.

But it’s Rogers himself who points to the chasm between where Nevada is, and what it could be. “You can get a pretty good education at UNR and UNLV,” Rogers said. “That doesn’t mean the university is doing what it ought to be doing. It should be a place where research is taking place, where the most creative and intelligent people go to talk, to think, to share ideas.”

It’s not the universities’ fault, Rogers says, that they still come up short. “It’s the community’s fault mostly, but also the governor’s fault and the Legislature’s fault. There’s no mandate from the people saying, ‘You are going to fund higher ed and K-12 education in the right way.’ ”

Although it’s unrealistic to expect Nevada’s universities to challenge Stanford, Berkeley or Cal Tech when it comes to funding, research or recruiting, “We should be able to compete against (the schools in) New Mexico, Utah and Arizona,” Rogers said.

The bruising 2009 legislative session didn’t help, although it could have been much, much worse for higher education. Gibbons’ budget called for a 36 percent cut, which unleashed Rogers’ wrath in the form of detailed weekly memos outlining the devastation that would be wrought by Gibbons’ budget, not just on education but also on critical services throughout the state.

The memos were “very well done, informative and helpful,” said Senate Minority Leader Bill Raggio, a Reno Republican and another passionate advocate for higher ed. “I used them.”

Rogers may have crossed the line from advocate to combatant with an op-ed in the Nevada Appeal of Carson City, in which he excoriated Gibbons as having “absolutely no regard for the welfare of any other human being.” That earned Rogers a written reprimand from the chairman and vice-chairman of the Board of Regents. The governor’s office declined to comment for this story.

Rogers’ mercurial temperament is the stuff of notoriety:

• In August 2004, just three months after being named interim chancellor, Rogers said he was revoking a $25 million pledge to UNLV because he was so frustrated by the higher education system. He changed his mind two months later, and the pledge was restored.

• In January 2007, Rogers announced his resignation as chancellor — and changed his mind 36 hours later.

• In August 2007, upset about criticism of his leadership by some regents, Rogers said his family decided not to make a $3 million gift to UNR.

Maybe one man’s tirades are another man’s passion.

“Jim Rogers wants to make progress, and he wants to make it now,” said Richard Morgan, who retired in 2007 as dean of the UNLV Boyd School of Law. “He’s big on efficiency, short on patience, aggressive, hard-charging and ambitious.”

Others put it this way: The strength of Rogers’ convictions comes not from arrogance, but from a deeply rooted belief that he was lucky enough to spot the best route through the brush, and it’s in everyone else’s best interest to follow.

There’s an upside to such transparency in a public persona, said Morgan, who was instrumental in building the law school and its reputation.

“Jim does not try to be subtle, so it’s easier to get a read on him than on someone who tries to hide the ball,” Morgan said. “You’re free to agree or disagree. He’s the first to acknowledge that he can be a bull in a china shop and a brusque guy, but his heart is in the right place.”

UNR Art Professor Howard Rosenberg, who during his 12 years as a regent clashed frequently with Rogers, said, “I never doubted his passion or his caring, although there were plenty of times when I disapproved of how he went about showing it.”

Does Rogers have a short fuse? Does he relish the bully pulpit?

“I do, and I do,” Rogers says. “I’m very demanding of other people, and myself. I do have a very short temper, and I wish I didn’t. But that’s the way I am.”

What he isn’t, Rogers said, is abusive.

“I never call people names,” Rogers said. “I never say to someone, ‘That was stupid.’ At the same time, I’m consistent, and I expect the people I work with to meet high expectations.”

Four years after Carol Harter quit as president of UNLV in 2005, butting heads with Rogers over who should call the shots at UNLV, both she and Rogers say they’ve developed a strong working relationship.

Rogers has worked with Harter, now the executive director of UNLV’s Black Mountain Institute for literary and cross-cultural dialogue, on several initiatives, and she has reciprocated by helping Rogers write portions of his memos.

Rogers told the Sun that if the Board of Regents takes his advice and does not renew UNLV President David Ashley’s contract, which runs through June 2010, he would be comfortable with Harter serving as the university’s interim leader.

Harter says in recent years she’s come to admire Rogers for his sheer tenacity.

“No matter how much criticism is heaped on him relative to his advocacy for funding education, he continues on,” Harter said. “We need that kind of champion — someone who has nothing to lose personally, who is in a position to be a strong advocate for both higher and lower education, and for funding both in a much more appropriate way.”

He is generally championed by a faculty that was initially dubious of his qualifications when he was named interim chancellor.

“We entered into this with some trepidation — we knew his reputation,” said UNR Professor Jim Richardson, longtime representative of the Nevada Faculty Alliance. But after sitting down with Rogers, faculty leadership endorsed him for the permanent job.

Rogers’ commitment to academic freedom, Richardson said, was demonstrated in 2005 when a UNLV economics professor was censured for a comment he made in class that a student complained was offensive to gays. Rogers overrode the censure — and paid for a conference on academic freedom at the law school, Richardson said.

“He’s been a strong defender of faculty,” Richardson said. “We’ve appreciated that.”

Sondra Cosgrove, a history professor at CSN and former chairwoman of its faculty senate, said Rogers never missed an opportunity to pump the importance of the community college system in the state’s economic recovery.

Cosgrove said Rogers kept in constant contact during the legislative session, providing updates on progress and asking pointed questions about the effect of funding inequities on students and staff.

“When the phone rang it was never his administrative assistant,” Cosgrove said. “It was always, ‘Hey, kiddo — it’s Jim.’ ”

Rogers’ preference for the personal touch also extended to philanthropy — where he set a high bar, donating more than $200 million to nonprofit organization, mostly for higher education.

In early 2002 Rogers met with Don Snyder, then-president of Boyd Gaming, to explore the possibility of UNLV mounting its first-ever capital campaign. Consultants were hired to test the university’s readiness for a proposed $250 million drive, and the potential level of community support.

The consultants’ report was blunt — UNLV lacked the heft to mount such a massive, multiyear undertaking, and community support was lacking.

“In true Jim Rogers fashion, he pushed ahead with a $500 million goal,” said Snyder, who retired from Boyd Gaming in 2006 and is chairman of the fundraising campaign. “There’s no doubt in my mind if he hadn’t had the backbone to do it, we would not be successfully completing the campaign this year.”

The next big push for Rogers will be the proposed health sciences system, which would pool the resources of the public colleges and the Desert Research Institute, creating new opportunities for learning and collaboration.

No time to relax, Rogers says.

“I’ve got one shot going through this life. I want to make sure I do as much as I can.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy