John Coulter / Special to the Sun

Thursday, March 25, 2010 | 2 a.m.

Reader poll

Related Document (.pdf)

Sun Coverage

During Las Vegas’ boom years, plentiful jobs were enough to keep the masses moving here.

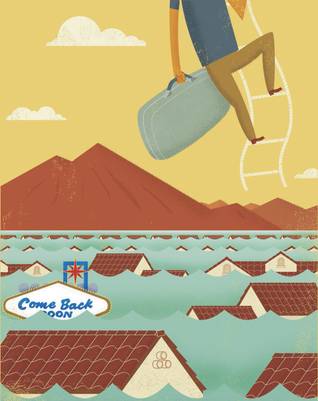

Now that the boom has gone bust, a new survey by UNLV researchers suggests a large share of valley residents see little reason to stay.

The Las Vegas Metropolitan Area Social Survey found 40 percent of locals want to leave the state.

The results are an indication of tough times, said Robert Futrell, a UNLV sociologist who led the study paid for by the university and the Southern Nevada Regional Planning Coalition.

Most Las Vegans, it seems, talk about moving at some point. The transient nature of the area — only 8 percent of us were born here — certainly contributes to that. But with Southern Nevada’s economy bumping along the bottom, shedding jobs as it goes, more might be thinking those thoughts.

“It seems some people would want to leave because jobs are unavailable and jobs were such a large force in drawing people here,” Futrell said.

Part of it, however, could be the sense some have that they’re trapped here — by being underwater in their mortgages (more than 80 percent of valley households) or unable to find an attractive job elsewhere (U.S. unemployment rate: 9.7 percent).

In reflecting on the survey’s results, local officials, residents and former Las Vegans cited the fact that local governments failed to foster a sense of community at the same pace developers threw up chock-a-block stucco homes.

Clark County Commissioner Chris Giunchigliani said that the large number of people who want to give up on the area shows government did not do enough during the good times to make the valley a place where people would want to live even during bad times.

“I know a lot of it is the economy. But this is when you want to have the amenities in place,” she said. “Shame on the county for not putting funding directly into ... programs like parks.” Park funding typically comes from developers.

County Commissioner Susan Brager, chairwoman of the Regional Planning Coalition, said she is surprised by the survey’s results. “Most people I talk to really love it here,” said Brager, who works as a real estate agent.

The study showed that 77 percent feel their quality of life here is at least “fairly good.”

But some Las Vegans who have left said they understand the feelings of those who are considering moving.

Matt Chernoff, 37, a musician and native Las Vegan, moved about a year ago to a tiny community three hours south of Portland, Ore., with his wife, Monica, 32, his father and friends. All had grown tired of Las Vegas.

On 10 acres, the group has started something of a commune, he said.

“Moisture in the air and a green environment: That’s the physical, biological reason we moved,” Chernoff said. “The more psychological was, we wanted to have a child and I wanted to raise a child outside of Las Vegas, knowing what it’s like to be raised in Vegas.”

“Vegas is like a flagship for gluttony,” he added.

Harrah’s Vice President Thom Reilly, a former Clark County manager who divides his week between Las Vegas and San Diego, was stunned by the survey’s results (“Forty percent? Wow, that’s huge.”).

But living in both cities has allowed Reilly to see firsthand the differences between Las Vegas and a city where a sense of community is cultivated.

“I’ve lived in San Diego less and know my neighbors more because I can walk to the restaurant, to the grocery store, to get my hair cut ... and I see people doing the same — the sense of community is heightened because you’re not always in your car,” he said.

The study was done to capture a picture of residents’ experience living in the valley and knowledge of the environment. Futrell hopes to secure funding to do the study every few years to track how attitudes change.

“There really hasn’t been a systematic study like this done here,” Futrell said. “But it’s crucial for policymakers and residents to think about who we are, what we think and what do we imagine for our future.”

Of the 664 households surveyed, 41 percent had some college education; 56 percent were married; 71 percent were white; 41 percent earned $40,000 to $80,000; 23 percent were liberal, 38 percent moderates, and 39 percent conservative; 41 percent lived in the suburbs; 45 percent had lived in their homes six to 15 years; and 13 percent were unemployed.

The study was designed to poll random neighborhoods. Most social surveys take random samples from large census tracts. The neighborhood focus helped identify residents’ feelings of discontent and how connected they are to their community or neighborhood.

The sense of belonging varies across the valley. Urban core residents had stronger attachments to their neighborhoods than those in suburban, urban fringe or retirement neighborhoods.

More people felt a stronger sense of belonging to the state and Las Vegas Valley than to the neighborhood where they live.

That can work against neighborhoods. The study makes the point that neighbors who feel disconnected “may be less willing to act together to solve neighborhood problems,” such as drug-dealing, vandalism or other crime.

Still, Futrell noted, “people seem to feel like they trust their neighbors, they just don’t interact with them.”

So how do you get neighbors to connect?

In focus groups, respondents told researchers “they perceive neighborhoods with parks as more tight-knit, healthy and stable.”

On the urban fringe — the far outreaches of new development where parks are more plentiful than in the urban core — park satisfaction is about twice as high as in the urban core. And, the study notes, “the farther one moves outward from the urban core neighborhoods, the more residents feel close to their neighbors.”

“People who lived around parks couldn’t talk enough about how important that was to their sense of neighborhood pride,” Futrell said.

These are “quality of life issues that we have to deal with, and things we need to look at as we do future planning,” Giunchigliani said. “We need to look at land-use plans and see where we might be impeding opportunities to create good neighborhoods. Do we really need block walls around every neighborhood? Do we need to force everyone into a homeowners association?”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy