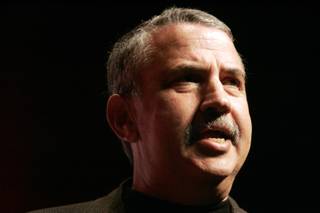

New York Times columnist and author Thomas Friedman speaks as part of the Barrick Lecture Series at Artemus Ham Hall on the campus of UNLV in Las Vegas Monday, March 28, 2011.

Tuesday, March 29, 2011 | 12:49 a.m.

Sun Archives

Beyond the Sun

New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman during a lecture in Las Vegas compared recent events in the Arab world to the fall of the Berlin wall and predicted that every Arab government will crumble within the next two years.

"This is not over," Friedman said of the revolutions that have swept the Middle East and Northern Africa since the beginning of the year.

Friedman was at UNLV Monday night scheduled to talk about environmentalism, climate change and the economy as part of the university's Barrick Lecture Series, but instead used his time to reflect on the revolutions sweeping the globe.

The three-time, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and author was in Cairo's Tahrir Square in late January when thousands of protesters took to the streets to demand an end to President Hosni Mubarak's nearly 30-year regime. Friedman covered the Middle East for more than a decade.

For the last 50 years, the Western world viewed Arab countries as a collection of "big gas stations," Friedman said. As long as they "kept the pumps open, the prices low and don't bother the Israelis too much," Western leaders let dictators do whatever they wanted.

Then Americans elected a black president with a Muslim grandfather and the middle name "Hussein," and disenfranchised Arabs suddenly felt empowered. Obama's election "planted seeds in the minds of the people," according to Friedman.

If Obama could become president, young Arabs reasoned they might finally be able to have a voice and a vote.

That hope, coupled with rising food prices, high unemployment and the frustrations of people living under totalitarian rule, facilitated the protests and government overthrows now dominating the news, Friedman argued.

"It wasn't about politics or parties or ideology," he said. "It was about people at the most human level. It was the incredible power of people losing their fear."

The world took notice, and the upheaval spread. First it began in Tunisia, where an unemployed computer scientist turned vegetable vendor burned himself alive to protest a police shakedown. Then it moved to Egypt. Now it has landed in Libya.

The success of Cairo's protesters stoked the flames.

"Egypt is not Las Vegas," Friedman said. "What happens (there) will not stay (there.)"

But for years, it did. Friedman said Mubarak was able to avoid international pushback and hobnob with Washington's elite by distancing himself from the Muslim Brotherhood, Egypt's oldest and largest Islamist organization, which Western leaders considered more dangerous than Mubarak.

"He was able to sit with Harry Reid and say, 'It's me or them,'" Friedman said.

The fight for liberty is more complex in Libya. Unlike Egypt, which has a large homogeneous population that banded together "to fight against dad" as Friedman put it, Libya is made up of a collection of tribal groups thrown together by colonialism. Its hodge podge of cultures and interests complicates a push toward democracy.

Friedman argued that reforms in Iraq prove democracy can prevail, and the country's transformation after American intervention presents a model for successfully building new political order.

But it also offers a sobering lesson, he said. Bringing democracy to Iraq cost $1 trillion, tens of thousands of casualties and a civil war.

Friedman predicted every Arab country will go through a similar transition, and he warned against the United States playing referee.

He said that while he agrees with Obama's decision to authorize air strikes on Libya, he worries because "when you bomb it, you own it."

Israel is stuck in the middle of the upheaval and a "deeply inbred government that's not particularly imaginative" compounds the country's problems, Friedman said.

"I'm afraid (Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin) Netanyahu will be the Mubarak of the peace process," Friedman said.

Netanyahu has a tremendous amount of leverage against Palestine right now and he should use it, Friedman argued. Mubarak was in power for almost 30 years and asserted his influence for reform only in the last week of his rule, Friedman said.

The problems facing the Middle East and Africa relate directly to America's struggles because of a what Friedman called a "feedback loop."

When food prices rise, instability rises. That causes oil prices to rise, which causes food prices to rise again. And the cycle continues.

Unfettered population growth compounds the crisis, as does America's reliance on oil. The United States is in desperate need of sound energy policy, both as an economic engine and to temper global climate change, Friedman said.

"We need a loop of our own," he said. "It's called energy policy. My beef with Libya is, if we are going to do something quick, really courageous, if we are really in the mood, how about an energy policy?"

Americans taunted the world's two most powerful forces - the market and Mother Nature - with unsustainable growth, Friedman said. He called the economic collapse "our warning heart attack."

"When you have no energy policy and no serious fiscal policy, you are doing uncontrolled experiments on the only planet we have," Friedman said.

Still, he remains despite the doom and gloom. But to keep that hope alive, Friedman said, Americans need to act.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy