Sunday, Nov. 25, 2012 | 2 a.m.

Sun coverage

After the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, Las Vegas became gripped in economic crisis. The tourism and convention business collapsed, workers were laid off or had their hours reduced, and there was talk about how destinations such as ours would suffer devastating, long-term consequences.

For many in Las Vegas, this is when D. Taylor, then the staff director and now the head of Culinary Union Local 226, stepped up big time.

“Right away, immediately, he was figuring out how to take care of the workers,” said Billy Vassiliadis, CEO of advertising and public affairs firm R&R Partners, which was managing the crisis for its key client, the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority.

The Culinary Union created Helping Hand, where laid off workers — thousands of them, not just union members — could enlist for unemployment and health benefits, food, rent, and utility and other assistance, all under one roof.

Steven Horsford, who worked for R&R at the time and who would go on to be elected to Congress, was helping coordinate the efforts among employers, the union and government agencies. “I realized quickly D. was an aggressive advocate for workers,” he said.

That crisis has passed, but the decades-long crisis of the American labor movement grinds on.

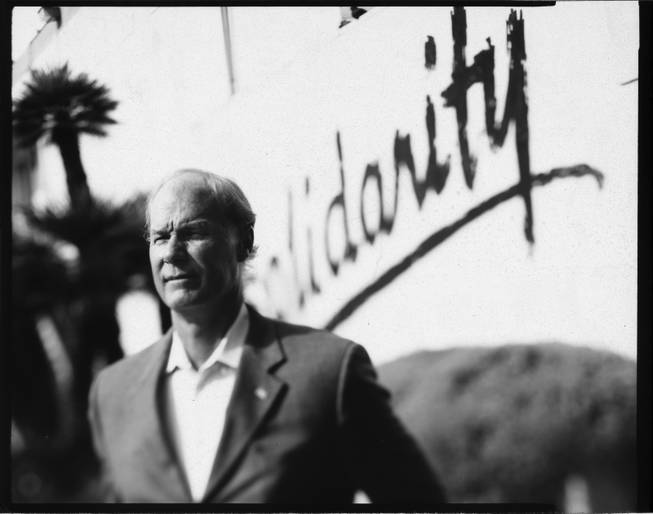

Into this long obsolescence of organized labor steps Taylor, who is expected to leave his post at the highly successful Culinary Union this month to become president of its parent union, Unite Here, which represents about a quarter of a million workers nationwide. Taylor, who will continue to live in Las Vegas, will replace another Las Vegas union legend, John Wilhelm.

Those who know Taylor — born Donald but forever known as D. — say he is a smart and capable leader and absolutely committed to his members, who come from the ranks of cocktail servers and bell staff, kitchen workers and cooks, housekeepers and porters.

In a wide-ranging interview, Taylor, 55, freely critiqued a stultified national labor movement’s failure to reach young people, Hispanics and blacks. And he expressed expansive goals for taking the “Las Vegas Dream” to service workers across the country.

“When people talk about the service economy, they’re usually talking about low wage, no benefits, high-turnover jobs,” he said. “What we represent is decent pay, good benefits, stable jobs for people who can raise a family and have a piece of the American Dream. Manufacturing might come back some day, but not to where it was, so we have to make service jobs the kinds of jobs that build the middle class, and I think that’s what Culinary Local 226 and Bartenders Local 165 represent in this town.”

Outside Las Vegas, however, Taylor is stepping into a different world, as he surely knows from his years as general vice president of Unite Here. Unlike Las Vegas, most cities offer a political and business atmosphere thoroughly hostile to unions, where expensive organizing battles end, at best, in tiny, incremental victories.

Win or lose, expect Taylor to be there to the bitter end.

•••

Taylor graduated from the prestigious Georgetown University School of Foreign Service. It took him six years because he was raised by a single mother and worked his way through school waiting tables.

He joined the restaurant workers union in 1979, was hired by the Culinary in 1981 and came to Las Vegas three years later. Membership has grown from 18,000 union workers in 1987 to approximately 60,000 members today, according to the union.

Although Taylor lives comfortably — as Culinary head he makes about $183,000 and his wife makes $127,000 as head of public policy for the Culinary Health Fund — the struggle of hard work for low pay seems to have stuck with him. People who know him say he’s probably more comfortable in the union’s ramshackle hall on Commerce Street than in fancy boardrooms.

“There’s no distance between himself and working people he represents. He wears his ball cap and his jeans and his sweatshirt and he speaks Spanish and knows the names and faces of his working troops,” Vassiliadis said. “Whether you’re with him or not, I’ve never had anybody question who he is and what he represents. It’s a mark of his character, and even if you disagree with him, you have to admire that.”

During a demonstration in front of Palace Station last year, Taylor was arrested along with some of his members as they protested Station Casinos, the company they have long and unsuccessfully sought to unionize.

Passion will only get you so far, however.

Taylor and the union have shown business, negotiating and political savvy.

The union has a close relationship with casino and hotel bosses, cognizant that unions struggle in industries and companies that aren’t profitable. “We’re intricately linked to the prosperity of the industry,” Taylor said. So, the union has supported industry expansion in other jurisdictions while often supporting gaming’s agenda in Carson City.

Jan Jones, former mayor of Las Vegas and now an executive with Caesars Entertainment, called Taylor a “responsible, thoughtful, business-minded advocate for workers.”

With these relationships forged, the union leveraged the Las Vegas boom: When new properties opened during those years, management didn’t stand in the way of the union. The union organized with the so-called “card check” process, whereby Culinary could sign up members and unionize by having them sign a card rather than going through an onerous and contentious election. This led to rapid membership gains.

Despite the mostly good relationship between labor and management, Taylor and the union have been tough negotiators, including using the threat of picketing. Taylor said a key to the Culinary’s success is instilling the ability in its members to work with management at times and oppose management at others.

Cindy Kiser Murphey, president of New York-New York, is on the board of the Culinary Health Fund with Taylor, so she’s been on the same side of the negotiating table as the board hammers out deals with health care providers.

“It’s definitely better to be on the same side of the table as D. He’s wickedly smart and very passionate about his protecting his members,” she said.

When it comes to politics, Taylor expresses disdain for the whole enterprise. Make no mistake, however, the union’s power and influence rests in part with its ability to eliminate political enemies.

The Culinary tends to husband and jealously guard its political resources, including perceptions — accurate or not — of its political influence, and then unleash them with overwhelming force.

Take Lynette Boggs. The Culinary teamed up with the police union to surveil the former county commissioner in 2006 and prove she was not living in her district as she claimed. She lost her re-election bid.

Taylor and the union have been particularly effective in mobilizing Hispanic voters, who in recent years often have made the difference in key statewide races.

There have been setbacks, including an endorsement of Barack Obama over Hillary Clinton in the 2008 Democratic caucus that divided the union and didn’t carry him over the top here.

For the most part, however, Nevada politicians would much rather stay clear of the Culinary’s bad side.

A final piece of the Culinary formula: enthusiasm. The spirit of the successful Frontier strike — a tenacious, six-year struggle — lives on. Without it, the Culinary’s threat of action wouldn’t amount to much. The union has successfully engaged its members. One need only go to a Culinary rally, during which thousands will march on their day off, to see a culture of solidarity and loyalty to the cause not usually seen in an America that has become mostly cynical about its institutions.

Add it up, and the union boasts strong membership numbers and excellent wages and benefits compared to workers in other markets.

These wages tend to push up wages citywide because non-union employers have to pay better to compete for good workers. It’s not an exaggeration to say that the union has built the Las Vegas middle class, such as it is.

•••

This brings us to Taylor’s future. Can the Las Vegas model of unionism and, with it, higher wages and better benefits for service workers succeed elsewhere?

The evidence points to no.

“Any union, no matter how great the leader is, well, they have an almost impossible task,” said Nelson Lichtenstein, director of the Center for the Study of Work, Labor and Democracy at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

“He’s in a cocoon,” said a Democratic operative who’s familiar with the labor movement.

The Strip offers easier conditions for the Culinary that won’t likely be replicated.

Unlike conventional hotels and restaurants in other cities, the Strip has been wildly profitable, discounting the recent brutal recession. Smaller profit margins amp up management opposition to unions.

The Culinary is lucky in that the Strip is controlled, mainly, by four companies. The union has agreements with three of them, which account for the vast majority of the rooms.

“With wall-to-wall unionism, resistance declines,” Lichtenstein said.

The opposite also is true. Unions increase wages, and thus labor costs. So, Lichtenstein said, “resistance to unionism increases the smaller the union movement gets because no one wants to be the only business in the market that’s unionized.”

And if that’s the case, private-sector labor unions are nearing extinction.

Private-sector union membership has fallen to 6.9 percent, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. That’s the lowest in more than a century. At one time, one third of private-sector workers were in a union.

The politics are worse.

The Republican Party platform this year, while attacking public-sector unions as expected, also bared its teeth at private-sector labor, calling for a national “right-to-work” law and the end of card check even for companies that want it.

Many of the wealthy benefactors who fund the party would happily preside over the death of the labor movement.

Democrats, meanwhile, have become less dependent on unions, especially private-sector unions. So they can’t be counted on to defend labor’s agenda, especially its efforts to make it easier to organize large employers such as Wal-Mart.

Taylor is, of course, aware of all this. He seems to be fighting a long war. “We have a different view of time,” he likes to say.

He has a laconic, soft-spoken demeanor, carrying around decades of victories and defeats like a weary insurgent leader. Bringing his fight national is the natural next step. The only step, really.

When asked about the bleak national outlook, Taylor, who has two daughters, said he’s looking to young people, who for too long haven’t played a key role in unions. “You can’t have a movement without young people. The big movements of the past 50 years — the civil rights movement and the anti-war movement — that wasn’t done by 50-year-olds. It was done by young people. They need a seat at the table.”

Likewise, Taylor said the movement needs to embrace Hispanics and blacks as the next organizers and labor leaders.

“The U.S. military is the best institution in America for developing African-American leadership. We should follow that example,” he said.

Finally, Taylor acknowledged labor’s long-term branding problem.

The image of unions, unfair though it may be, is of lazy workers in passe industries or government, led by corrupt “union bosses” if not “union thugs.” Given that so many Americans have very little contact with the labor movement, this is all they know.

“People are very smart, and they know neither political party is going to deliver the kind of economic equity we need to have. That only comes with the union movement. So we need to figure out how we embrace that and brand ourselves like that because that’s the truth.”

Sun researcher Rebecca Clifford contributed to this report.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy