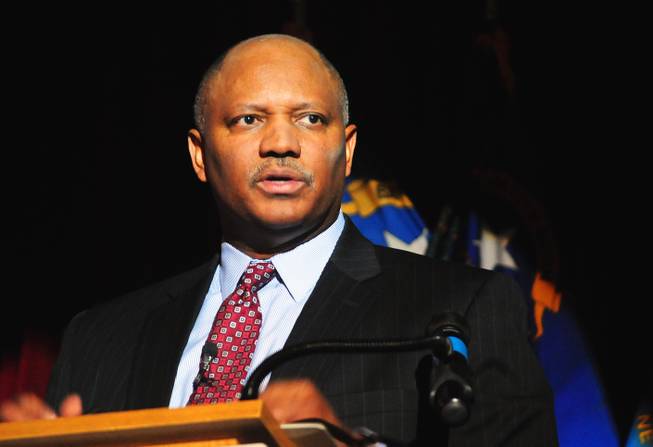

Clark County Schools Superintendent Dwight Jones delivers his second annual “State of the District” address on Monday, Jan. 14, 2013, at Western High School. Jones unveiled a new online “Open Book” portal, which makes the district’s financial information public, and touted the district’s academic gains last school year.

Published Tuesday, March 5, 2013 | 8 p.m.

Updated Wednesday, March 6, 2013 | 1 a.m.

Related stories

- Clark County school superintendent: ‘We are going to need some support’ (2-24-2013)

- Six Questions: CCSD’s Dwight Jones on tax proposal to fix aging schools (10-12-2012)

- Superintendent: ‘I am here to implement and see through reform’ (3-11-2012)

- Colorado’s Dwight Jones offered job as Clark County schools superintendent (9-29-2010)

Clark County Schools Superintendent Dwight Jones announced Tuesday evening that he is stepping down from the nation's fifth-largest school district.

Jones, who was hired in October 2010, said he is leaving to take care of his ailing mother.

His mother had been ill for some time, but her condition worsened over the past few weeks, Jones said. For about a month, Jones had been traveling to Dallas to care for his mother, he said. Jones contemplated a leave of absence to be with his mother in Texas for a short period, but he said he realized he "couldn't do both jobs."

"I just need to support my mother. She needs me 100 percent," Jones said. "She is important to me and my family."

• • •

Jones came to town promising new reforms to turn the system around. When he arrived, Clark County had one of the lowest test scores and graduation rates in the nation.

To "turn the ship around," the former education commissioner of Colorado installed a version of the "Colorado Growth Model," a new way to measure student achievement by annual improvement rather than proficiency scores. This model served as the backbone for the Silver State's waiver from the federal No Child Left Behind Act.

Jones also worked to make the district more transparent by launching the state's first school ranking system, which rated schools on a one- to five-star scale. High-performing schools were given more autonomy while low-performing schools were given more support.

Throughout his tenure, Jones sought to bring a more personal touch to his turnaround efforts. He launched the "Reclaim Your Future" initiative, going door to door to persuade dropouts to return to school. He also started a new mentorship program, reaching out to the larger community to help its youngsters.

Greater emphasis was placed on principals to identify struggling children to help them graduate. Through the federal turnaround effort, several of the district's worst-performing schools were overhauled with new principals, teachers and resources, translating to a dramatic improvement in school culture and student achievement.

Through it all, Jones never gave up on students who demonstrated the will and desire to graduate. Despite financial constraints, the superintendent allowed seniors to take summer classes and even a fifth year to receive their high school diplomas.

Jones pointed to the district's first August graduation that honored students who were on the cusp of dropping out but persevered to pass their proficiency exams and coursework — even after most of their peers had graduated in June.

"I'm just proud of that kind of work," Jones said. "I hope we changed the conversation around setting high expectations for our kids — to do everything humanly possible to support them."

• • •

Jones is leaving before much of his reform efforts have borne fruit, but he said he is optimistic about the direction of the School District. He said he hopes the School Board will continue "to stay the course."

"I think we've made a lot of progress, but there's much more work to be done," Jones said.

Jones said he is most proud of his staff and teachers, and what they have been able to accomplish during his short time here.

"I know budgets here have been horrible, but teachers have done an amazing job," Jones said. "They have done a great job with less."

Jones has no immediate plans for employment but said he will move back to Colorado, where he maintains a home. Jones said he will fly between Denver and Dallas to be with his mother. His wife, who was a public school volunteer and helped with local foundations in Clark County, will return to work in the Denver public school system, Jones said.

Jones said he hopes to return to education someday, but for now, he is committed to helping support his family.

"The timing is certainly never good, but illness has no set time," Jones said. "This has been a very difficult decision, but I have been honored for the opportunity to serve."

Jones informed the School Board of his decision Tuesday night. His last day will be March 22.

• • •

School Board President Carolyn Edwards said she was "stunned and dismayed" by Jones' decision to leave his post just halfway through his four-year contract. Jones has been paid $396,000 per year, including benefits, according to TransparentNevada.com.

Edwards said she doesn't believe Jones was looking for an easy way out of the many challenges he faced in Clark County, nor did she think he was abandoning the reform efforts he started here.

"This was a very hard decision for him. He's not taking this lightly at all," Edwards said. "He's committed to the work he's been doing here. He's been invested in this community."

The average superintendent tenure nationwide is about three years. All of Jones' immediate predecessors — Walt Rulffes, Carlos Garcia and Brian Cram — had stayed at the helm for at least five years.

Jones would have stayed for that long if it weren't for his ailing mother, Edwards said. Jones' father has already died, which explains why it was so important for Jones to care for his mother, Edwards said.

"I understand he needs to do this," Edwards said. "He will be sorry for the rest of his life if he doesn't."

• • •

Jones saw the district through one of the toughest periods in Las Vegas history, guiding its schools through the aftermath of the worst recession in over 50 years.

During his tenure, the district experienced multimillion-dollar cuts, which caused class sizes to balloon and programs being cut.

Jones also inherited a challenging student population, the majority of whom are minority students from low-income families. Nearly a quarter of Clark County students live in poverty, and 53,000 students don't speak English at home.

Jones acknowledged these challenges, but refused to allow them to become scapegoats for his administration. "No excuses," he often said.

Jones' tenure was characterized by reforms big and small, but also several missteps and mishaps.

Jones created plenty of enemies when he went to battle with the local teachers union, one of the largest unions in the state. To shift more resources to the classroom, Jones called for a freeze on all employee salaries.

The teachers union revolted. The ensuing barrage of union demonstrations took a toll on Jones' public image, one that he would never overcome for the remainder of his tenure. Frustrated teachers began leaving the district in droves.

When an arbitrator decided against the district last spring, Jones was dealt his first major setback. Jones said the binding decision forced him to cut more than 1,000 teaching positions, raising class sizes by an average of three students.

During the subsequent contract negotiation, Jones went on the offensive, immediately calling an impasse and sending the matter into arbitration.

This time, Jones prevailed. The superintendent promised the $34 million award will be used to hire more teachers for classrooms, which are among the largest in the nation. (Union officials declined to comment about Jones' departure Monday evening.)

Jones was dealt his second major blow when he called on Southern Nevadans for support to address the district's overcrowded and deteriorating schools.

The district wanted to raise property taxes to help pay for school repairs and maintenance and to build two new schools. In November, voters overwhelmingly rejected the district's tax initiative.

This setback caused Jones to work harder to win over community trust.

Jones' final project — the Open Book Portal — tries to make the district's finances more easily accessible to the public. By going on the website, residents are able to see how taxpayer dollars are being allocated and make suggestions on how to run the district more effectively and efficiently.

• • •

Even with the support of the School Board and much of the business community, Jones was not without his faults.

When Jones refused to release preliminary graduation data to the public, critics called him out for being transparent only when it suited him.

Others were skeptical of Jones' highly paid consultants, pricey technology initiatives and close ties with the "education reform" movement sweeping the nation.

Some criticized Jones for a slower-than-expected rate of improvement. Others criticized Jones for moving too fast with his reform efforts.

Jones — the district's second black superintendent — received some of his highest accolades and harshest criticisms from members of his own community.

While he tried his best to address the needs of a minority-majority school district, Jones was unable to solve some of the district's deepest inequities.

The School District continues to have the nation's second highest achievement gap between white and minority students, and has the notoriety of expelling its black students at a rate three times higher than other races.

During Jones' tenure, the district also failed to boost its English-language learner students, 90 percent of whom failed to pass the high school proficiency exam last year.

• • •

Despite these shortcomings, Jones will likely be remembered for being an agent of change in one of the worst-performing public school districts in the nation.

"Dwight is a forceful, courageous visionary," said state superintendent Jim Guthrie. "We won't forget him soon."

The Clark County School Board is expected to set a date for a discussion on Jones' replacement on Wednesday morning. Deputy Superintendent Pat Skorkowsky will assume the role of acting superintendent once Jones steps down March 22.

Regardless of who his replacement will be, the transformational legacy Jones leaves behind will continue, Guthrie said.

The state — which has already adopted the "growth model" — will soon roll out its own version of Clark County's school rating system and implement a teacher evaluation system that Jones worked closely with Gov. Brian Sandoval to develop.

"Clark County educates 70 percent of Nevada's children," Guthrie said. "So goes Clark County, so goes the rest of the state.

"We're not going to lose any any momentum here," he continued. "We're not going to lose any ground."

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy