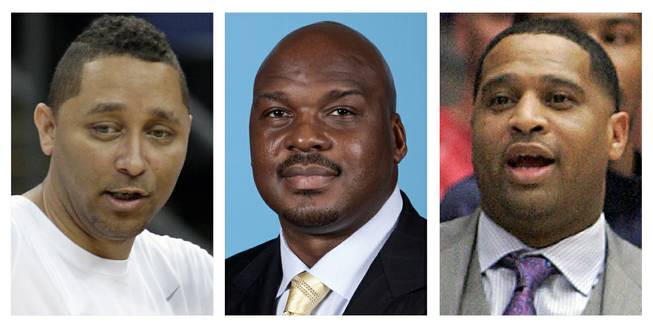

AP

These file photos show, assistant basketball coaches Tony Bland, left, Chuck Person, center, and Lamont Richardson. The three, along with assistant coach Lamont Evans of Oklahoma State, were identified in court papers and are among 10 people facing federal charges in Manhattan federal court, Tuesday, Sept. 26, 2017, in a wide probe of fraud and corruption in the NCAA, authorities said.

Wednesday, Sept. 27, 2017 | 1 a.m.

As the associate head coach at Auburn University, Chuck Person knew he had plenty to sell to the elite high school basketball players he recruited. He was the NBA Rookie of the Year in 1987 and a deadly shooter with a colorful nickname, the Rifleman, who spent 13 seasons in the league. He also earned a championship ring as an assistant coach with the 2010 Los Angeles Lakers.

Person was revered at Auburn, his alma mater, along with his former teammate Charles Barkley, for leading the Tigers to their first NCAA men’s basketball tournament, in 1984.

Now he might find himself ostracized from Auburn and college basketball. Federal investigators zeroed in on Person, 53, in a 32-page complaint released on Tuesday that accused him of bribery, wire fraud and conspiracy. According to the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York, Person accepted $91,500 for steering pro prospects (and current Tigers) to an unnamed financial adviser, who was a cooperating witness for the government. Person then illicitly gave a portion of those kickbacks to the players.

Why was Person so confident in his ability not only to coach teenage hoop stars into future NBA millionaires but also to deliver them to the financial adviser?

“When you’ve coached Kobe Bryant, worked with Phil Jackson, it goes a long ways,” Person said to the federal informant on a recorded telephone call, according to the complaint.

Recorded conversations, videotapes and evidence of Person’s cash payments — as well as complaints that outlined allegations of similar transgressions by three other assistant coaches at prominent programs — laid bare the worst-kept secret in college athletics: Student-athletes (the NCAA’s preferred term) have been bought and sold in pursuit of championship glory and a healthy percentage of their future earnings.

Past scandals in college basketball have tarnished iconic coaches like Jerry Tarkanian and Rick Pitino and storied programs like the University of Kentucky, to name a small fraction.

Until Tuesday, criminal charges were almost unheard-of. In the past, it was up to journalists to act on tips from disgruntled players or agents to bring the scandals to light. Then the NCAA, which has never had enough resources to police all of its members, would investigate and mete out punishment.

In recent years, many colleges under suspicion have pre-empted that process. They have hired outside law firms (often stocked with former NCAA employees) to investigate accusations and, if necessary, to enter into a plea negotiation with the NCAA, preferably one that does not turn off the spigot of athletic revenues.

Person and the other coaches implicated in the federal complaints will need a different kind of lawyer — the criminal variety. Oklahoma State’s Lamont Evans, Arizona’s Emanuel Richardson and the University of Southern California’s Tony Bland were accused of bribery for accepting payments to steer players to specific agents.

The complaints might pressure these coaches to cooperate with the government, perhaps resulting in even more coaches’ facing criminal charges.

In Person’s case, the allegations suggest a scheme born out of convenience and a simple calculus. Rashan Michel, an Atlanta-based tailor of bespoke suits for a clientele of professional athletes, was named as a co-defendant. Michel, the complaint said, promised the financial adviser that he could deliver college basketball coaches because he made their suits and had “access to the locker room” and “the kids.”

Besides, Michel told the adviser in salty language, NBA players make “way more” than football guys and 10 of them over the next five years would generate enough revenue that he and the adviser would be able to sit back and do “absolutely nothing.”

Person passed on about $18,500 to the families of two athletes in recorded meetings where warnings about secrecy were paramount, according to the complaint. But he was not above displaying greed. He asked the informant to cut Michel out of the financial loop, the complaint said, and tried to double dip with another unnamed financial adviser, who declined to enter a pay-for-play agreement.

In a wry footnote, the FBI agent who prepared the affidavit noted that Person had not done his due diligence on the financial adviser/informant. If Person had done a simple internet search, for example, he would have found that the financial adviser was facing securities fraud allegations leveled by the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Person apparently was oblivious. He vouched for the informant to a parent, saying that the informant was his personal financial adviser and Barkley’s, as well.

And Person demonstrated how he molded young men.

“Your personality and the way you do things can’t change,” Person instructed a player. “Don’t flaunt the stuff you get and, you know, don’t change the way you speak to people — that’s very important, too, and character, which we talk about all the time.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy