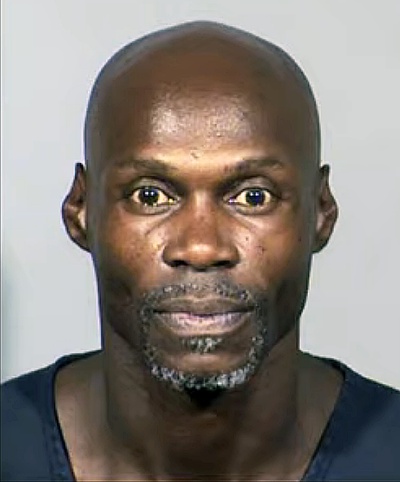

A protester holds a sign featuring a photo of Byron Williams in front of Metro Police headquarters on Martin Luther King Boulevard Thursday, Aug. 13, 2020. Williams died in police custody on Sept. 5, 2019.

Saturday, Sept. 5, 2020 | 6:27 p.m.

Related Content

A year ago today, Byron Williams was pedaling his bicycle before dawn when Metro Police tried to stop him. Less than two minutes later, pinned by an officer, he repeatedly uttered “I can’t breathe.”

Less than an hour later, Williams, 50, was dead.

If Williams had not been a Black man he would have never been “hunted and chased down” just because he didn’t have a safety light on his bike, his attorney Antonio Romanucci said.

“This is not even a property crime,” Romanucci said. “He was chased. He was run down. He was restrained. He was cooperative. He was not violent,” Romanucci said this afternoon a virtual press conference, accompanied by Williams’ sister, niece and cousin.

The Clark County Coroner’s Office last October ruled Williams’ death a homicide. Williams died of methamphetamine intoxication, but a “prone restraint” used by an officer contributed significantly to his death. Lung and heart diseases also contributed, officials said.

Romanucci said today that lawyers are preparing to file a wrongful death lawsuit against Metro on behalf of the Williams family. Benjamin Crump, a prominent civil rights attorney, is also representing them.

The team is seeking additional body-camera footage from Metro that wasn’t broadcast publicly but viewed by the family in the aftermath of Williams’ death.

In it, the family has said, Williams is heard pleading that he couldn’t breathe, while officers mocked him, saying things like “ain’t (sic) no one coming for you.”

Metro has denied requests for the footage, citing an open investigation, Romanucci said. A lawsuit complaint requires evidence that offers a clear picture, Romanucci said.

“We don’t want to file a lawsuit that’s going to be attacked, because it’s not factually correct, because they hid the evidence from us,” he said.

About 5:48 a.m. Sept. 5, 2019, Williams was riding his bike on Martin Luther King Boulevard and Bonanza Road when a two-officer patrol team tried to pull him over because he didn’t have proper lighting and it was dark, police said.

Williams didn’t stop, ditched his bike, and ran, scaling two walls before surrendering at a nearby apartment complex. Williams was lying face down when one of the officers straddled him and put his knee on his buttocks. That's when Williams is heard saying he couldn’t breathe.

The video shows an officer telling Williams that he couldn’t breathe because “you’re tired of (expletive) running.” An officer later tells him, “I got pressure on your butt, that’s all.”

Moments later, another officer is seen on footage kneeling on the man’s legs. Police have said Williams resisted arrest because he was concealing a bag of meth and prescription pills, which they later found.

As they were hauling him off, Williams’ body appeared to be unconscious, the video shows. Officers summoned an ambulance, which arrived 14 minutes later, at 6:08 a.m. That’s around the time the officers all turned off their body cameras, said police, noting that they’re able to do that when a situation appears under control.

But Romanucci alleges they turned them off to “hide the truth.”

Unlike other in-custody deaths of Black Americans across the country, Williams’ death didn’t receive attention outside of Las Vegas because of “suppression of evidence,” Romanucci said.

“I don’t know what could have happened last year,” Romanucci said about demonstrations additional body camera video might have sparked. “In a way it’s sad that Byron didn’t get the due and the attention that he deserved, but he’s getting it now. Byron in his death, I promise you, will make a difference.”

The Williams family also disagrees with Metro’s practice of releasing the decedents’ criminal histories, amplifying a narrative that’s favorable with police, they say.

Williams had a criminal record in Nevada and California and had absconded from house arrest at the time of his death. But the arresting officers — Officers Benjamin Vazquez and Patrick Campbell — didn’t know of Williams’ history when they encountered him, officials said.

Clark County Sheriff Joe Lombardo last year told the Sun the officers didn’t profile Williams based on his race, but said officers “could have done a better job” handling the scenario.

Vazquez and Campbell were attempting a “simple” pedestrian stop to talk to Williams, who decided to run, Lombardo said.

Following the death, Metro changed how it deals with suspects who say they can’t breathe, Lombardo said. Officers are now required to place suspects on their side, sit or stand them up.

But for Williams, it’s too little too late, his family says.

They remember him as a joyful, athletic man who seemed to always be sporting a smile.

“Their job was to simply place the handcuffs and take him into custody,” said Tina Lewis-Stevenson, his sister. “But they chose to elevate the situation and murder him. And we are devastated by this and we definitely want justice.”