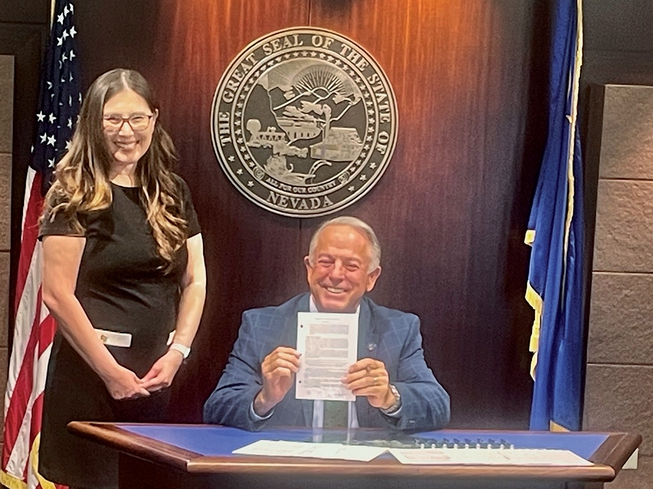

Clark County Family Court Judge Sunny Bailey, left, and Gov. Joe Lombardo mark the ceremonial signing of Senate Bill 411, which establishes a statewide diversionary court program for at-risk adolescent youths with autism. Bailey in 2018 spearheaded the successful Detention Alternative for Autistic Youth Court in Clark County, which will serve as a model for the statewide program.

Tuesday, July 18, 2023 | 2 a.m.

Gov. Joe Lombardo, surrounded by advocates for youths with autism, judges and public defenders, conducts a ceremonial signing of Senate Bill 411, which establishes a statewide diversionary court program for at-risk adolescent youths with autism. The signing was Monday, July 17, 2023, at the Grant Sawyer State Office Building.

Mental health care in Nevada

Nevada is primed to become the first in the nation to establish a diversionary court program statewide for at-risk adolescent youths with autism, a move officials say will help children on the spectrum stay on a path of success.

Gov. Joe Lombardo held a ceremonial signing Monday in Las Vegas for Senate Bill 411, which allows family courts statewide to establish an “appropriate program” for children diagnosed with or suspected to have autism spectrum disorders. The bill passed unanimously through the Nevada Legislature.

“It shows you how much effort it takes to have successful legislation,” Lombardo told attendees at the Grant Sawyer State Office Building, which included autism advocates, judges and public defenders. “The thing that surprised me with today’s bill is that it hasn’t happened before today. And that’s unfortunate, but now, fortunately, we’re moving forward as a community.”

A child assigned to the program must be made aware of the terms for successful completion of the program, including probation or other informal supervision, and the court must also provide benchmarks to “ensure that every child is making satisfactory progress” toward completing the program.

Clark County’s 8th Judicial District Court launched a similar diversionary program in 2018, spearheaded by juvenile court Judge Sunny Bailey, who is the mother of an autistic child, she told the Sun.

That program, which is called Detention Alternative for Autistic Youth, or DAAY Court, came about after Bailey was assigned a case involving a delinquent on the spectrum. She and others from the district attorney’s office volunteered on the side to develop a tailored supervision program to fit that child’s needs.

DAAY Court “addresses clients’ access to appropriate services to reduce recidivism in the juvenile justice system,” according to a flyer posted by the court. Treatments for youths in the program can include mental health counseling, applied behavioral analysis (ABA) therapy, recreational therapy, referrals to community resources and providers, among others. It is open to youths on the spectrum, ages 10 to 18.

Bailey knew eventually she had three months’ worth of cases involving children with autism blocked off on her calendar, she said.

“I think it’s amazing to see how much of the community can come together to support our youth,” Bailey said. “We don’t advertise. Everything is word of mouth. I’m surprised at how many people do know about us. And I think it’s one of those things that people don’t realize the need and how strong that need is.”

And based on the success Clark County has seen, the hope is the program can be an even more essential tool in rural areas of the state, Clark County District Attorney Steve Wolfson.

“Judge Bailey created this court here in Clark County, but the needs are statewide,” Wolfson said. “This law now allows other jurisdictions to create similar courts and hopefully model after what Judge Bailey has created.”

The bill was introduced by state Sen. James Ohrenschall, D-Las Vegas, who also works as a public defender specializing in delinquent cases. Ohrenschall told the Assembly Committee on Health and Human Services during a May 15 hearing he was pressed by constituents who voiced a desire to expand the program statewide to help with kids who may not have had a proper diagnosis, or need advanced intervention to address behavioral issues, such as when the child may be prone to violent outbursts.

“The one thing we really hoped was that there would be programs like this across the state for children who maybe have not yet received treatment or have not yet been diagnosed to try and get them the therapeutic treatment that can help them succeed and not end up in the criminal justice system or the delinquency system,” he said in the hearing.

Bailey told lawmakers during that same hearing approximately 1 in 36 youths in the U.S. are diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, but it’s hard to pinpoint for sure how many end up in the criminal justice system.

A recent survey suggests there could be upwards of 100,000 adults in the U.S. prison system who are on the spectrum, and even that might not be an accurate count, Bailey told lawmakers. But by establishing a statewide program, young offenders with autism may be able to get help before they reach adulthood, when the courts could be less understanding of offenders with cognitive or behavioral health ailments.

“The justice system isn’t set up to handle kids,” said Darin Imlay, a Clark County public defender. “Especially kids with mental health issues. So any kind of program, any type of diversion, to get them out of that system, because there’s such a cookie-cutter approach when you get to the criminal justice system. And it doesn’t work for everybody.”