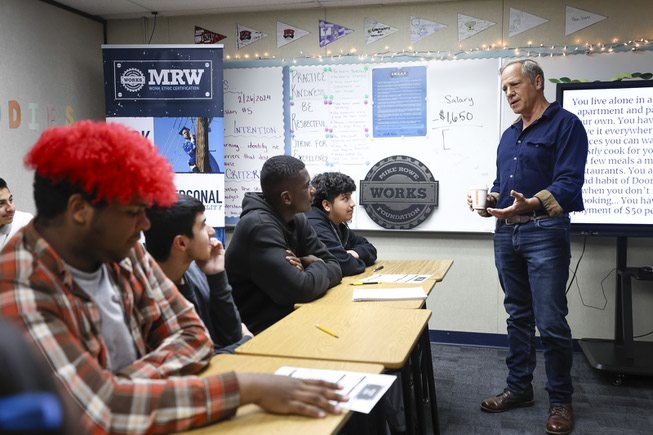

Mike Rowe, creator and host of the TV series Dirty Jobs and founder of the mikeroweWORKS Foundation, speaks to students at Western High School Monday, Feb. 26, 2024. Rowe’s visit to the school was to announce a new program, created in partnership between his foundation and the Engelstad Foundation, with the goal of providing full-ride scholarships for trade programs to students upon graduation.

Tuesday, Feb. 27, 2024 | 2 a.m.

The foremost celebrity advocate for blue-collar professions visited a Las Vegas high school Monday to promote the trades and announce a new vocational school scholarship that will help students prosper while working with their hands.

Television personality Mike Rowe, known for creating and hosting the “Dirty Jobs” reality show, dropped by Western High School to announce the new Warrior Pathway Program, which will cover full-ride scholarships to trade schools for Western students who stay the course to graduation.

There are bright young people out there who don’t connect with bookish academics and bachelor’s degrees.

However, “over the course of the last few decades, we’ve elevated one form of education at the expense of all the others. And so today, we do have a skills gap,” said Rowe, who founded a nonprofit, the mikeroweWORKS Foundation, that promotes the vocational training that society needs to function.

“If I have my way, initiatives like this will be happening in every ZIP code in every county in every state, because the skills gap is not unique to Clark County, and underserved kids are certainly not unique to this,” he added.

In the freshman studies classroom that Rowe visited, not every student knew what they wanted to do as adults — but there were some noble dreams in the room, from musical artist and interior designer to restaurant owner and cosmetologist.

Until then, they are teens with chores like washing dishes.

Dishes don’t wash themselves, Rowe said. And there are other basics that need working hands to maintain normal life processes — turning the lights on requires an electrician. Flushing the toilet requires a plumber.

For students who might want to learn the skills needed to keep lights on and water flowing, there is trade school. To pay for that training, there is the Warrior Pathway Program.

The program is inspired by the mikeroweWORKS Foundation’s SWEAT Pledge, which stands for Skill and Work Ethic Aren’t Taboo. It has four main principles: work ethic, personal responsibility, delayed gratification and a positive attitude.

All incoming Western freshmen will be required to take the mikeroweWORKS Foundation’s Work Ethic Certification Program, also based on the SWEAT Pledge, that aims to give students employability skills.

Students who elect to stay with the program after their freshman year will have enhanced access to trade-focused internships and jobs. If they complete the program through their senior year, they will be offered scholarships to two-year or shorter technical training programs. There are no grade requirements, only good attendance and behavior.

The estimated value of these scholarships is $4.5 million, with funding provided by the local Engelstad Foundation.

Western Principal Antonio Rael said he hoped that of this year’s 700-student freshman class, 50 will have trade school paid for after graduation in 2027.

“Western High School serves a community that is historically underserved, and we have students that have historically been the furthest from the college readiness gap,” Rael said. “The idea is, how do we take these great children, these great families and avail the opportunity if they’re willing to put in the work? It’s not a handout program — it is, you do the work, we will create a pathway for you to get there.”

Kris Engelstad, CEO of the Engelstad Foundation, said the philanthropic organization provided scholarships to about 200 students a year, but she recognizes that traditional academics aren’t the only pathway.

“There are other kids who aren’t going to go to four-year colleges,” she said. “It doesn’t mean they can’t be successful.”

Rowe said a lot of young people say they want to go to university because they hear it is supposed to unlock what’s needed to improve their life.

He said there’s nothing wrong with a four-year, liberal arts degree — he has one in communications. But it’s expensive, and the emphasis has left many well-paying, necessary jobs unfilled.

“One of the things we say at mikeroweWORKS often is, not all knowledge comes from college, but skill is a matter of degree,” he said. “A big part of what we’re hoping to do is not denigrate a four-year education by any means. But it’s to simply say, look, a cookie-cutter approach and a one-size-fits-all approach to educating our kids is not only short-sighted, it’s doomed.”

With “Dirty Jobs,” which ran off and on from 2003 to 2023, Rowe embedded with people who do demanding, messy or uncommon skilled labor. He said the trades could be intoxicating to people who pursued them, showing accomplishment in real time. He said people told him the people he worked with seemed happy, even if they were crawling through sewers — they were happy because they were proud, he said.

He says he makes today’s trades resonate with young people by showing them how technology intersects with manual work.

Not long ago, he was in a wide-open field — perhaps in North Dakota, he said — with a technician working on a massive piece of Caterpillar machinery. Bulldozers can’t exactly be brought into a mechanic’s garage and put on a lift to troubleshoot, he noted.

He asked the worker what the most important tool was that he had in his toolbox.

“He pulled out an iPad and crawled under the bulldozer and took a film of the broken part and sent it back to the shop. It was diagnosed there. A bunch of magic stuff happened — you know, internet hookups and satellites and stuff. Whole problem was diagnosed with the aid of that tool,” he said. “I’ve seen a thousand examples of stuff like that. And when you show that to a kid, suddenly, it’s less mysterious, because they’re seeing a tool they understand.”

Andrea Villalpando, 15, wants to own a restaurant. After a chat with Rowe, she learned that if you have a dream, you need to work hard.

And of those kitchen chores that lots of teens have: “Before you know it,” Rowe said, “you’ll be owning the restaurant where the dishes need to be done.”