Mojave High School principal Antonio Rael stands overlooking the quad at the school in North Las Vegas on Wednesday, August 24, 2011.

Tuesday, Aug. 30, 2011 | 2 a.m.

The Turnaround: Mojave High School

KSNV examines the Clark County School District's turnaround efforts at Mojave High School.

Related stories

- At Chaparral, clean house, new faces, fresh start (8-29-2011)

- Principal David Wilson: Laying down the law to change the culture (8-29-2011)

- Five struggling schools embark on a journey to improve education (8-28-2011)

- Sun to track progress of 5 struggling schools (8-28-2011)

- Discussion: School District’s top officials sit down with the Sun (8-28-2011)

- Shifting demographics demand greater urgency in improving schools (8-28-2011)

- How community views education must change if schools are to be fixed (8-28-2011)

Map of Mojave

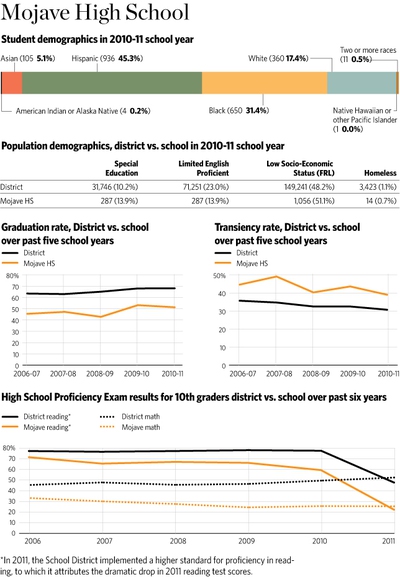

This is Mojave High School’s sorry reputation: Because it was proclaimed a “persistently low-achieving school” by the Clark County School District, students living within its boundaries were allowed to attend different schools last year. More than 1,000 jumped on the offer.

Mojave’s football team is the preferred opponent at other schools’ homecoming games because the hapless squad is considered a pushover that will keep the home crowd in good spirits. Only a quarter of 10th-graders are proficient in math, reading and science, and half of the school’s students won’t graduate. The school has been branded with a vulgar nickname, inspired by the wafting odors of a nearby pig farm.

So the question is, when the School District looked around for a new principal for Mojave, why did Antonio Rael raise his hand?

“Mojave High School is a dream job for me. When the position opened, I was ecstatic,” he says. “I feel a great sense of responsibility to this campus because what they (the community) have gotten from Mojave High School in the past is not what they have deserved. The reality is, Mojave is not what it could have been.”

Rael is 34 and a veteran of arena football. That experience might serve him well at Mojave.

•••

It is the calm before the storm, a quiet summer morning that finds Rael poking around his new office, which is begging to be decorated beyond a potted plant in the corner. Filling his office will be the least of his worries.

For the past five months, he has been filling the ranks of teachers who, lured either by the challenge or by pay raises or both, said they’re willing to join his campaign to turn Mojave around.

“Teachers are the silver bullet,” Rael says, smiling. “We didn’t want to look past the good talent on this campus, so we hired some good people back. But certainly, we hired a lot of people from around the district. I really feel like we have a tremendous team.”

Rael is, for all intents and purposes, building a school from scratch. The old Mojave wasn’t doing well, based on numerous criteria, including a federal mandate, adopted in 2001, that schools improve student performance. No Child Left Behind requires students to improve each year, and for the pace of that improvement to quicken over the years.

Mojave failed to meet those goals the past six years.

Improving the school wouldn’t come cheaply. But as it happened, the School District this year received $8.7 million in federal stimulus money allocated through the state to help. Mojave’s piece of the pie: $2.5 million parceled out over three years.

The grant has strings attached; things at Mojave must change. The district implemented a “turnaround” at Mojave, replacing the principal and making everyone from teachers to custodians reapply for their positions.

It’s one way local and federal officials think change can be effected at the struggling school. About 80 percent of Mojave’s staff are new to the school this year.

Rael, a Phoenix native and the son of a construction manager, would be the change agent. The state grant laid out its expectations for reform. Some are dramatic — recruit and train high-quality teachers from across the district to fill Mojave’s classrooms, for example. Some are relatively simple — extend the school day by 20 minutes. Rael, a math teacher by training, wants to implement an engineering program with the help of UNLV that he hopes would reinvigorate the school’s math program.

“Our greatest challenge is changing the perception of Mojave High School,” Rael says. “We really want this to be a place where parents say, ‘I’m proud my son, my daughter graduated from Mojave.’ ”

•••

As the start of school approached, the buzz of activity was returning to campus. On this day, Rael — tall, thin, muscular — is wearing a dark suit, maroon shirt and tie despite the scorching summer heat. With the kind of firm handshake that has gripped a lot of footballs, Rael greets a few teachers who came in early to prepare classrooms.

He saves a fist bump for an assistant principal. “It’s going to be a good year,” he says. “I’m fired up!”

Rael is proud of what he has accomplished this summer and hopes his staff and students feel the same. In fact, the goal for Rael’s “new Mojave High School” is trumpeted on large, green-and-orange signs all across campus: “Pride.”

School spirit at Mojave, while not measurable by a test, is at a major low.

One night in July, four teenagers broke into the school. They trashed a number of offices, stole computers and spray-painted swastikas and gang signs on a half-dozen walls. One of the vandals was later identified as a Mojave student. So much for pride.

“The problem we have right now is that our children aren’t proud of their own school,” he says. “When our children begin to take pride in our school, our community will follow.”

Rael, who lives just four miles from campus, has some experience with pride. During his three years as principal at Fremont Middle School, test scores rose and the occurrence of graffiti plummeted, including a 10-month run without a single tag.

Rael has high expectations for campus cleanliness. During the summer, district maintenance crews replaced windows, power-sprayed the gum-stained concrete grounds, polished the gym floor and painted tables and walls. At the very least, Mojave had “that showroom shine” when school opened this week.

•••

Sprucing up the campus is something the School District does every summer. Replacing about 100 staffers out of 140 is something the district had never attempted at the high school level.

They were hired over spring break with the help of Assistant Principal Greg Cole, who brings a decade of experience teaching special education in Clark County. He culled new ones from 300 people who wanted to work at Mojave.

Money may have been an incentive for some. Teachers were given $1,750 signing bonuses for the first year and additional pay for good student performance on tests in the second and third years of the grant.

In selecting the staff, Cole and Rael picked the teachers they hope will build positive relationships with high school students. That’s no easy task: Teaching is one thing. Connecting with them is another.

“We felt like if we were going to turn this thing around, we have to bring people on campus who aren’t afraid to let kids know they love them,” Cole says. “If you don’t make that connection with the kids, then we’re stuck in the same place.”

Over the summer, teachers at every district turnaround school attended a special three-day workshop to help them build strong relationships with one another and with their students. Rael believes when students know someone cares, it will keep them away from the temptations of the streets.

•••

Stacks of geometry textbooks and boxes of school supplies sit atop the empty desks in Deb Brown’s first-floor classroom.

Brown is a returning Mojave teacher, a nine-year veteran who begins her 13th year with the district. The 47-year-old with short brown curls is feeling lucky.

“I’m getting a big rush. It’s all positive,” Brown says of the changes. “We’re looking forward. Looking back doesn’t accomplish anything.”

Earlier in her career, Brown was on the other side of the turnaround as a new teacher coming into a troubled school in El Paso, Texas — where a school turnaround meant changing teachers, school colors and even the mascot. Mojave is keeping its green and orange colors as well as its rattlesnake mascot, but change will still prove hard to swallow, Brown says. “No one believes it’s going to be a piece of cake.” “It’s not going to be smooth.”

As the head of the mathematics department, Brown will be in charge of raising Mojave’s math test scores by 5 percent each year for the next three years. It’s a tall order, considering only a quarter of 10th-graders passed the math portion of the High School Proficiency Exam.

Hoping to better engage students, Mojave will partner with UNLV in the coming months to implement the engineering program that will connect math concepts with real-world situations. Interested students will be able to take a robotics course or build remote-controlled cars — the kind of curricula more typically found at the district’s magnet schools and career and technical academies.

•••

Rattlers football coach Joe Delgado is handing out shoulder pads and protective gear to about 100 players in the locker room. There’s excitement in the musky air.

Although the improvement grants may be used only for academics — new electronic “smartboards” and teacher training, for example — extracurricular programs such as athletics are also important in the turnaround process, Delgado says. For some students, being part of a team — even a losing one — is the only reason they show up to school.

“Kids have flat-out told us if it wasn’t for football, they’d be running with the wrong crowd, basically in the streets and getting into no good,” Delgado, 37, says.

Mojave has not had a winning team since former coach Tyrone Armstrong led it to the 2007 playoffs with an 8-3 record. The team went 0-9 last year, and 2-7 two years ago.

Mojave is tired of being a “lay-down school,” an automatic win for other teams, Delgado says.

Still, winning isn’t everything in Delgado’s book. The point of the football program, he says, is to ensure students have options after they graduate, whether it’s an academic scholarship or an athletic one.

“There are going to be a select few who are going to get scholarships to play college football,” he says. “But we tell them the best thing to do is to make the best of your time in the classroom, because that’s going to be the easier way to get the scholarship.”

With encouragement from Rael and Delgado, about a quarter of the team attended summer school this year so they would have enough credits to be eligible to play this season. And, for the first time in years, 44 Rattlers paid to attend a weeklong high school football camp in Utah to drill and bond over the gridiron.

“It’s a big family environment right now, and that’s what I love about football,” Delgado says. He hopes to see his teams’ school spirit translate to the rest of the student body.

“Our first win will be huge not only for the football team but for the entire school,” he says. “Just seeing all the new faces here, people all pumped up to be here, I’m excited. Everyone is looking forward to that challenge of turning this school around. I think positive things are going to be happening soon.”

•••

Rael is facing a few dozen parents at Nellis Air Force Base’s military child education forum.

They’re a tough crowd. Most high school-aged students at Nellis are zoned for Mojave, but most parents say they know better than to send their kids there. Mojave’s poor reputation precedes it, even as far away as a Tokyo military base.

A middle school mom who recently moved onto Nellis breaks down in tears as she confronts Rael. “Why should I send my child to public schools here? Tell me. I don’t want my son to fail.”

Rael encourages parents to visit Mojave. It’s different now, he insists, knowing all the while it’s a hard sell.

Years of negative perceptions can’t be wiped away so easily. But Rael is energetic, his impassioned voice rising above the snide remarks muttered under heavy breaths.

“We’re a new school. We’re not what Mojave High School has been in the past,” he says. “Visit the new Mojave and come see for yourself.”

After the two-hour meeting, Rael meets with some of the parents one on one, trying to assuage their fears. Some, like Alisa Conley, whose 13-year-old daughter, Spirit, starts her freshman year this week, are optimistic about the “new Mojave.”

“Just by the attitude of the new principal, it gives us hope,” Conley says. “I’m excited. We’re looking forward to these changes.”

Others, like Karyn Hoss, aren’t so sure. Her 14-year-old son, Hunter, is zoned for Mojave, but won’t be attending the school as a freshman.

“I heard about the gang violence and vandalism,” Hoss, 35, said. “I would feel safer if my son went to Legacy.”

The community’s view of Mojave is “cautious optimism,” Rael says, wringing his hands. But with all the new changes, he says the School District has set Mojave up to succeed.

“There have been some good and some bad here in the past, but we will all be good looking forward,” he says. “We have some challenges ahead of us, but we’re going to win those challenges one child at a time.”

That includes RayEna, Rael’s 14-year-old daughter who started this week as a Mojave freshman.

Mojave High School is Rattler Nation, but really it’s home to underdogs.

Minutes from the Nellis Air Force Base the school is nestled near Commerce Street and West Ann Road, an area littered with foreclosed homes.

The school is attended by many students who are underprivileged or at-risk. After Mojave failed to meet No Child Left Behind standards it became one of five Clark County Schools determined to do a 180.

In order to make the turnaround a reality, Mojave has implemented new faculty, extended the school day by 20 minutes and is geared towards boosting school spirit.

“The problem we have right now is that our children aren’t proud of their own school,” Mojave principal Antonio Rael explained an August interview. “When our children begin to take pride in our school, our community will follow.”

- Year built:

- 1997

- Mascot:

- Rattle Snake

- Principal (Year Hired):

- Antonio Rael (2001)

- School motto:

- “Promoting Achievement, Creating Success”

- Mission Statement:

- “The Mission of the Mojave High School Community is to provide a safe learning environment that will empower students to develop excellence, pride, respect, and skills necessary for future success.”

- Enrollment:

- Approximately 2,000

- School Report Card:

- 2010-2011

Compiled by Gregan Wingert

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy