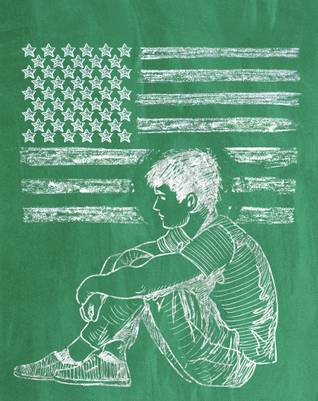

Shutterstock.com

Sunday, May 26, 2019 | 2 a.m.

Editor’s note: Some names and details have been changed or omitted to protect the identity of individuals.

Growing up in El Salvador, Felix loved school, especially math, and hoped to become an accountant. But shortly after his 16th birthday, his plans were derailed by a single phone call.

The call was from someone affiliated with MS-13, a notorious gang in El Salvador. The caller told Felix that he owed the gang a large sum of money, and that if he couldn't pay up, gang members would rape and kill him and his family.

That was 2014, one of the most violent years in El Salvador’s recent history as the murder rate jumped 56 percent. In the face of growing poverty and inequality, gangs had become increasingly influential, and it was common for children as young as 14 to be recruited—or forced—to join.

In a panic, Felix called his mother, who had immigrated to Las Vegas when he was 4 years old.

They agreed that the best option was for him to come to the United States. His mother sent money for bus fare and immigration fees (mostly to pay off gangs stationed at checkpoints), and Felix set off alone on the 2,000-mile trek through El Salvador, Guatemala and Mexico.

On day nine, he reached the Rio Grande River at the U.S.-Mexico border. Hungry, thirsty and afraid, he managed to swim across before U.S. officials caught him. He was detained for several days, at which point he was able to call his mother. She arranged for him to fly to Las Vegas.

Felix arrived in Southern Nevada unable to speak a word of English. Stepping off the plane, he wandered around the airport in search of his mother, whom he hadn’t seen since he was a toddler. She took him to live with her in a one-bedroom apartment shared with her boyfriend and a roommate.

Like many immigrants from Central American countries, Felix came to the U.S. fleeing violence at home. Unfortunately, hardship followed him to Las Vegas. The following is his account of his experiences.

• • •

The central Las Vegas high school in which Felix enrolled two weeks after his arrival to the U.S. had a large population of students learning English and one of the highest populations of student refugees in the Clark County School District.

On his first day, Felix met Brad, an instructional coach certified to teach English, French and Spanish. He has extensive experience working with those from different cultures and backgrounds, including traumatic ones.

“[My students] are fleeing violence, they’re fleeing poverty, they’re fleeing some of the most dire situations on the globe, and they somehow end up here,” Brad explained.

Initially, Felix couldn’t figure out why an alarm kept going off during classes. Brad explained that the bell meant it was time to switch classrooms.

“I was totally lost,” Felix said.

Gradually, things got easier as Felix adjusted to the American education system and picked up more English. But at a certain point, Brad noticed something troubling: Felix couldn’t stay awake in class.

Shortly after arriving, Felix had started working 50 hours a week, per his mother’s orders, to repay her for getting him out of El Salvador and eventually for rent and other expenses.

Six days a week, from 5 p.m. to 2 a.m., Felix worked a low-wage job at a restaurant, then commuted home by bus, a journey that took nearly two hours at that time of night. He slept a few hours before showing up to school by 7 a.m.

Eventually, Brad asked Felix why he couldn’t stay awake.

“You could tell he was hungry and tired, so I tried to connect him to all the services I knew,” Brad said. “But there’s only so much you can do as a teacher. You have to be very distant.”

Despite being overworked, sleep-deprived and under stress at home—his mother often put him down for not learning English quickly enough, or not making more money—Felix worked hard in school, earning a 3.8 grade-point average. After failing to pass the Nevada Proficiency Test, a controversial state graduation requirement for all students that was eliminated in 2017, his high school granted him an extra year to finish.

Felix dedicated himself to studying for the exam, attending school on Saturdays and staying late on weekdays, all while getting a very different message at home: Quit school so you can earn more money.

Felix had other plans and begged his mother to let him finish.

“Every single fight was the same thing over and over,” he said.

On Dec. 24, a few days after giving his mother his paycheck to cover half their rent as usual, Felix came home from work to find his clothes and belongings in boxes outside the apartment.

“She was like, ‘You are not a good son. You’re not the person we want for our life,’ ” Felix said.

And if he came back, his mother and her boyfriend warned him, his life would be in danger.

In the following weeks, Felix lived everywhere and nowhere. In the used car he had bought that year for $500. At his girlfriend’s home. Eventually, he scraped together enough money to rent an apartment for $600 a month. Lacking money for furniture, he slept on the floor.

When school resumed after winter break, Brad realized something wasn’t right with Felix. He told a colleague of his concern and asked him to listen in as he spoke to Felix, who immediately started crying as he confessed to what had happened.

“He crumbled,” Brad said.

Brad connected Felix to resources for at-risk youths in Clark County, namely the Title I Homeless Outreach Program for Education (HOPE) and Communities in Schools of Nevada. Both organizations helped Felix acquire food, a mattress, blankets, a microwave, a toothbrush and other things he lacked.

Felix continued to work over 40 hours a week at a restaurant and to study for his proficiency. Finally, he passed, and Brad and other teachers shifted their focus to the next task: getting Felix to college.

Felix still wanted to become an accountant, but given his uncertain immigration status, could he really make it to college? He applied to the College of Southern Nevada and UNLV, but neither accepted him.

But Brad knew about a program at Nevada State College called Nepantla, specifically designed for first-generation college students. Felix applied and was accepted on a scholarship.

He started the academically rigorous program right after high school graduation, but quickly wondered if he was in over his head.

“He could pass the proficiency, but he couldn’t write essays on the social construction of race,” Brad explained.

With few other academic resources, Felix sought help from Brad. He attended classes during the day, worked from early evening until midnight, and then stopped by Brad’s house to write essays. Brad continued to inform his school supervisors of the situation, but eventually, they told him it was no longer necessary because Felix had graduated.

With Felix’s housing situation still in flux, he would often fall asleep on Brad’s couch after a night of studying.

“It was probably the 70th time he fell asleep at my house that summer at 3 o'clock in the morning ... that I realized, ‘I just can’t let this one go,’ ” Brad said.

It wasn’t just that Felix had no one else to turn to—he continued to face occasional threats from relatives relating to his fallout with his mother—it was also that Felix was motivated, bright, curious and kind.

“How can you not love him?” Brad said.

Felix had long thought of Brad as a paternal figure. And in that first year of college, Brad and his husband, Karl, started to see Felix as a son. Initially concerned about how Felix would perceive their sexuality (support for same-sex marriage and gay rights is low in El Salvador), it quickly became clear that that wasn't an issue for Felix.

“We were like, ‘Are you okay with us being gay?’ And he’s like, ‘I don’t care.’ And that’s really great to have that acceptance,” Brad said.

So in January, Karl and Brad invited Felix to live with them. Now, Felix calls them his dads.

“I didn’t want a kid at all. But I’m super-happy to have one,” Brad said. “It’s been the best thing for us. It’s brought us together as a family.”

As far as Felix’s immigration status is concerned, they hope to settle his case in the future.

“He did all the paperwork. He did everything right, but they closed his case administratively, which means it’s not open, it’s not closed, it’s not yes and it’s not no,” Brad said.

Lawyers have advised them to wait to reopen the case until the political climate becomes less hostile toward undocumented immigrants.

• • •

Though some aspects of Felix’s story may sound exceptional, Felix was one of thousands of unaccompanied minors from El Salvador to come to the United States in 2014. That year, the United States saw an uptick in young people fleeing the country, mostly boys between the ages of 14 and 17, said Randy Capps, director of research for U.S. programs at the Migration Policy Institute.

Many left El Salvador for similar reasons as Felix.

“As they got old enough, they would start to get pressured by gangs and extortionists in El Salvador. That’s a very common pattern,” said Capps, adding that conditions there have begun to improve in the past year.

In Nevada, there are an estimated 29,000 El Salvadorans, making it the third-largest immigrant population in the state with over five percent of all immigrants here hailing from the Central American country. Young El Salvadoran immigrants face similar challenges as other immigrants when adjusting to life in America, including language barriers, trauma, interruptions in their education, stress as a result of resettlement and culture shock, said Ignacio Ruiz, assistant superintendent for CCSD’s English Language Learners division.

Some of them, like Felix, are part of a larger population of CCSD students considered “active refugees,” which can include asylees, victims of human trafficking and unaccompanied minors. There are 661 such students in CCSD schools now.

In addition to adjusting to school in the United States, young immigrants may also face stress and pressure at home.

“The family is often struggling economically, and there’s usually an expectation that the kid is going to work once they reach age 16 to help. So there’s always that struggle,” Capps said.

Jasmine Coca, director of immigration services at Catholic Charities of Southern Nevada, said she has witnessed firsthand these tensions between Central American immigrant children and their parents because of a family’s financial situation and uncertain legal status.

“I’ve had to talk to my clients about the importance of a kid going to school, and that it’s not just about working,” Coca said.

Under such circumstances, many students who arrive in the United States don’t end up as lucky as Felix — halfway through college, a manager at a restaurant and on track to become an accountant. They might not find themselves at a high school with as many resources as the one Felix attended, and they might not meet a mentor and advocate like Brad.

Nonetheless, it’s clear to Brad and Karl that it wasn’t just luck that got Felix to where he is today. It was also his exceptional grit, dedication and love for learning.

Felix himself is a little more modest.

“I just keep trying,” he said. “Even though life used to be really hard and it seemed there was no solution for it, there’s always a solution for it.”

This story originally appeared in the Las Vegas Weekly.