Rod Davis grew up 10 miles outside Birmingham, Ala. He left the South to escape Jim Crow laws.

Monday, Jan. 16, 2012 | 2 a.m.

View more of the Sun's opinion section

J. Patrick Coolican

This is what life was like for Dorothy Stepp and her family in Louisiana in 1957.

Her father was a pipe-fitter, and her mother worked in the kitchen of a cafe — she wasn’t allowed to be out with the white customers. Dorothy and her 19 siblings picked cotton and worked as maids for white families.

“We shared beds. We shared clothes. We shared everything,” she said.

One day her father’s foreman went on a supply run and left her father in charge of the white work crew

Her father had a sharp sense of humor. That’s the only explanation, she said, for what happened next. He never came home. Stepp’s mother went to the work site to try to find him.

“She said to them, ‘He must be somewhere. He got paid today. He knows to bring the money home.’ ”

Stepp’s mother searched the site and found a mound and a shallow grave where her husband was buried. They moved the body for a proper burial, and the coroner’s autopsy showed that Stepp’s father had been beaten to death, or near death, with a blunt object, and then buried. Stepp said six men murdered her father.

A newspaper account shows a big and emotional funeral.

The men never faced justice.

His murder is shocking to us now but wouldn’t have been in that time or place. The Jim Crow South could be dangerous for blacks, who were subject to routine terror and capricious violence. By one tally, there were at least 3,650 lynchings across the South between 1889 and 1929. Riots, in which whites would loot and burn black areas, were not uncommon. Census data often show sudden black population collapse in some areas, when all the blacks would be driven from a city or county — just gone.

Stepp was angry, but her mother told the children, “Those six men were bad men, but I don’t want you to grow up hating a whole race of people for those six men.” Her mother raised all those children on her own.

Dorothy Stepp’s brother wound up in the service, based in Las Vegas. Dorothy and a sister came here in the early ’60s — she can’t quite remember exactly when — and never went back. She now has seven siblings here.

Remembering a hero

It was the era of the Rat Pack and Wayne Newton in Las Vegas, but in 1964, another famous public figure made his way to the desert. Martin Luther King Jr. visited Las Vegas, stumping for the Civil Rights Act. King spoke at the Las Vegas Convention Center on April 26, 1964 — less than a year after he delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. About two months after his visit, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act on July 2, 1964, banning major forms of racial discrimination and ending segregation. That same year, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to King.

Stepp was one of nearly 6 million black Americans who fled the Jim Crow South from 1915 to 1975. When it began, 10 percent of blacks lived outside the South. By the time it was finished, nearly half did.

I recently discovered the amazing story of what’s known as the Great Migration from a 2010 book by Isabel Wilkerson, “The Warmth of Other Sons,” a beautifully told and insightful story that follows three people on their journey. (To be clear, there was plenty of racism in the North, but not the codified caste apartheid of the South.)

I went looking for more Las Vegans who had come here seeking freedom, and they weren’t hard to find.

I met with a group whose stories of life under Jim Crow and escape and liberation are incredible history. They did what they did because it was what they had to do for freedom and a better life. Nothing particularly remarkable about it, they shrug.

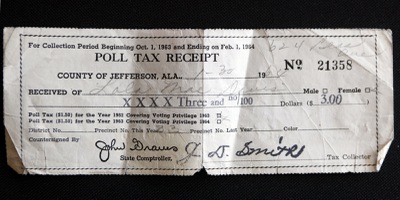

Rod Davis grew up 10 miles out of Birmingham, Ala. He still has a 1952 receipt for the poll tax, the levy issued to try to prevent blacks from voting.

Davis said he’s still amazed at how Rosa Parks worked up the nerve to sit in the front of that bus.

He couldn’t take it anymore and knew he had to go.

“I would have been dead,” he said. “I wasn’t going to obey those rules anymore.”

What rules? Separate schools and public facilities. Political organizing was a life-threatening activity. But also the small, insidious humiliations: having to allow a white person to move ahead in line at the market, having to step off the sidewalk or walk on the other side of the street. Having rocks thrown at you when you pedalled your bicycle or walked to school — there were often no buses for black children.

Davis left two weeks after the infamous church bombing that killed four girls.

“I just knew I wanted to do something with my life,” he said.

Millie Blanford knew it, too.

“I told my husband there is something somewhere better,” she said.

James Joyner left the Florida panhandle for Evanston, Ill., and enlisted in the Air Force, where he served eight years. He and a white friend left a base in Texas once to go to the movies, and Joyner was ordered to the “colored” section — he had forgotten about Jim Crow. They immediately returned to the base and never ventured off it again.

Like the others, Joyner had joined a 20th century version of the Underground Railroad. You can still trace the southern lineage of northern and western cities by the bus and rail lines of the time and simple geography.

Davis got on a bus with $250 and a bag of chicken. The room chuckled at the reference. They had to bring their own food because they couldn’t be sure anyone would sell to them once they were on the road.

The journey was often hard. They were on the verge of freedom but not yet there. Helen Mingleton wrote a prose poem recalling the journey as a young girl from Houston to California: “stars that fell from the black skies to land in wild animals’ eyes.”

If they rode the bus, they lived under the usual rules — sit in the back or on the floor, no use of the bathroom. If they drove, it was no fun road trip. They raced to escape, relieved themselves on the side of the road and drove miles out of their way to reach a place that was safe for a black family to sleep. Mingleton, her parents, an aunt and three siblings slept in their ’51 Buick because motels wouldn’t take blacks.

Each of these people managed to persevere and succeed. They were and are teachers, business people, police officers and occupational therapists. Their parents drilled into them the value of education. Davis became the only black Firestone franchisee in the country, with three stores in Southern California.

“They just needed the opportunity!” Mingleton said.

Make no mistake, though. As Stepp said, “You don’t forget it. You never forget it. It’s a part of you.”

And we should never forget.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy