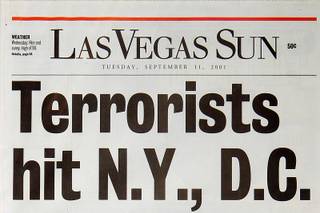

Daniel Hulshizer / AP

Thick smoke billows into the sky from the area behind the Statue of Liberty, lower left, where the World Trade Center towers stood, on Tuesday, Sept. 11, 2001. The towers collapsed after terroists crashed two planes into them.

Sunday, Sept. 11, 2011 | 2 a.m.

View more of the Sun's opinion section

Remembering 9/11

- 10 years after tragedy, is Las Vegas any safer?

- Reflecting on how Sept. 11 has changed our lives

- 9/11 memorial T-shirts fashioned into art at UNLV

- Jon Ralston: What we’ve lost since Sept. 11

- Sun Editorial: Sobering anniversary brings memories, reminders of what’s important

- 10 years later, Las Vegas Sun photo of girl with flag still resonates

- Palo Verde students preserve 9/11 tradition — and teacher’s legacy

Sun archives

Read the stories that ran in the Las Vegas Sun on the following dates:

When I exited the subway at the World Trade Center stop that morning, paper was floating down from a clear blue sky.

Sept. 11, 2001, was election day in New York City and my final day with the Gotham Gazette, an online politics and policy magazine based in lower Manhattan.

I was supposed to be in the Bronx that morning, following a mayoral candidate as he cast his ballot. But I had overslept — I was staying at a friend’s house in Queens — and was traveling to the Gazette offices to apologize to my editor. But then I would be dispatched to the chaotic streets to cover what I could of the evolving tragedy.

I would watch pieces of the towers, huge sheets of metal, catching the air and gliding to the ground like kites losing their wind. A woman would say, “Those are people,” pointing at the burning towers. “No, they’re not,” I would reply.

But she would be right. And some would be falling, limbs flailing.

I remember most vividly another woman screaming over and over: “Nobody loves nobody anymore.”

I had the benefit of having a job to do. My mind was occupied trying to get a story — the story of a generation — and this distracted me, at least partially, from dwelling on the horror of it all.

I also had the curse of having a job to do. I couldn’t run away like nearly everyone else, or run away without feeling like a professional failure.

I did run, in fact. And it has always gnawed at me, knowing I missed important details by working at a safe distance and relying on firsthand accounts instead of direct observation.

A part of me will always feel like I should have died that day charging toward the towers to do my job.

•••

The first plane struck the north tower while I was in the subway, oblivious.

Confused by the chaos, I walked to an old office building a couple of blocks from the World Trade Center to talk to my editor, Jonathan Mandell.

We watched on a small newsroom television as a plane hit the south tower. The office shook violently. It was just after 9 a.m.

We discussed how to cover the story. And he gave me his press pass and told me to go out on the street for an hour and find something that fit the publication’s political mission.

In retrospect, the assignment was absurd: Municipal election delayed by national tragedy? Self-absorbed mayoral candidates put off by thousands dead?

But we didn’t know the scope of what was happening. I took it on myself to report the story straight on.

I ran west from the office toward the burning towers, which were mostly obstructed by other buildings. Dazed men and women in business attire scurried the other way.

A lone police officer standing in the middle of the street, his arms held wide, told me to turn around. He looked as scared as I felt.

I could have pushed ahead, I’m sure. But I was relieved to have an excuse to turn around. Pure cowardice.

I walked a half-circle around the World Trade Center blocks, going from the east side of the buildings to the north, then the west.

I remember running away twice, as each of the towers fell.

I remember happening upon Mayor Rudy Giuliani after the first tower fell. He was surrounded by a small entourage. He walked fast and looked angry, but calm.

A cameraman struggled to keep up. I helped hold him up as he walked backward, camera trained on the mayor, through an ash-covered street.

I remained at a safe distance, interviewing people in the streets.

They talked about dodging the falling bodies.

“Glass and concrete were flying down,” one man told me. “I went under a bench. People started jumping, and they would literally explode when they hit the ground. I ran toward them. I don’t know why. Maybe you never know if someone might be alive.” He was walking through a courtyard at 4 World Financial Center when the first plane hit.

I felt — still feel — ashamed of not witnessing it for myself, of being a secondhand observer to history. I passed on a front-row seat out of fear.

I asked the people who were fleeing how they felt — that clichéd question that rings so false in the ear of any experienced reporter.

•••

I never did get what I would consider a good story.

I walked to NYU, to the journalism building where I had been a student months before, and borrowed a computer to write and email a story to my editor. Then I called him and my parents.

My editor, who I admire to this day, rewrote the story — that’s what editors do, of course — and added it to his and another editor’s report.

This is some of what I think I wrote:

“At 10 a.m., the first building collapsed. It was slow motion movie-life; an explosion of flames, the building crumbling, the great rumble reaching the crowd, and then a cloud of ash, first in a bubble low to the ground.

“Momentarily, the crowd was paralyzed, not seeming to accept what had happened ...

“The cloud spread ... The cops yelled: ‘Run, run. That’s asbestos in there. Don’t walk, run!’ People ducked in buildings, behind cars, in locked doorways.

“Covered in about an inch of the finely ground white-grey ash, an African-American woman who now looked white was limping alongside a man in the middle of Fulton Street. ‘It’s OK, I’m here, I’m here, I’m here, it’s OK, I’m here,’ the man said to her, as she cried.

“People were stumbling east away from the towers, trying to escape. Some hid in doorways, trying to shield their faces.

“After the cloud had settled a little, Mayor Rudolph Giuliani walked through the street, looking straight ahead. ‘Everyone should remain calm and head north above Canal.’ He told the people surrounding him that he had contact with the president. ‘Stay calm.’ ”

•••

I left New York the following year to take a job in Victorville, Calif. And I have spent the past decade at newspapers, learning that life can’t be sustained by a career alone.

I married Emily, who I had met in college. We have three children. They are what is most important to me now, although I still love journalism.

I resisted writing about that day. I don’t talk about it. I try not to read about it. When I run across programs about it on TV, I change the channel. I had done a good job keeping the emotions from that day bottled up.

Then on Tuesday a 32-year-old man walked into a Carson City IHOP and shot 11 people with an AK-47. He then turned his gun on himself.

The restaurant is about a mile from my house. A few days before, I had suggested to my wife that it would be a good place to take our children.

The shooting, of course, was not on the scale of the attacks 10 years ago. But the community grief, the sense of unease and vulnerability, felt the same.

I took a break from work Tuesday to pick up my 5-year-old daughter and 3-year-old son from school. A mom told me the shooting “makes you want to crawl under a rock with your kids and hide.”

My children were surprised and happy to see me at school. After I took them home I made them big sandwiches for lunch and gave them extra hugs before returning to work.

No regrets about that.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy